Green Cove Watershed could be the most cherished stream in South Puget Sound. Olympia offers art shows to promote “the importance of salmon to our community.” The Evergreen State College cultivates “creative, critical thinkers … for environmental work and leadership.” However, if I want to understand stewardship, I listen to the swampy stream that sits between them.

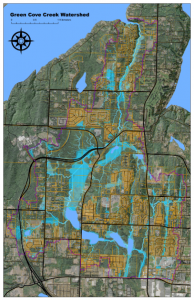

Most people I meet don’t know Green Cove Creek. We don’t see Mud Bay Road as an indistinct saddle marking the Southern divide. We don’t notice how our road causeways have walled its headwater swamps into cells, or where our polluted discharge trickles in through glacial swales. We guess at how many different kinds of salamander have survived. They wait for warm night rains to crawl our roads.

We don’t count the Green Cove chum thwarted at Country Club Road culvert from ever making their nests. We don’t gather or forage. When we need water, we extract it from injected well casing. When we need food we bring it in on trucks. We don’t see the land in front of us, and so how can we understand where we are going?

This discordant gap between the social narratives in our heads, and our relationship to the land in front of us may be the cornerstone of our ecological crisis. Each day we express in miniature, our relationship with the Salish Sea. The most brutal parts of our colonial project are mostly complete, and unremembered. Our new homeland has been tamed, made quiet, marked with deep wounds, drying out slowly with road ditches.

There is a quiet struggle at Green Cove Creek. Twenty years ago the City was impelled to buy the Grass Lakes, and signed the Green Cove Watershed Plan — another treaty. South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group is just starting to explore the salmon-bearing habitats, a project recommended 20 years ago. Project managers grimace at the fish-barrier culvert buried deep under road fill (have we ever abandoned a road, for the love of a stream?). A volunteer counts salmon redds.

We must enforce good planning at the permit counter.

The Squaxin Nation struggles at more urgent sites. Between Streamteam, Stormwater and Parks, the City affords a little work here and there. A couple middle school teachers sustain a science and service program, and Native Plant Salvage Foundation lends a hand. Capitol Land Trust stopped buying land in Green Cove when Thurston County started hoarding all  our Conservation Futures money to offset prairie development. Sometimes groups of college students wander by and look. Government biologists count mud minnows. Community activism ebbs and flows with each new subdivision proposal. Does this add up to stewardship?

our Conservation Futures money to offset prairie development. Sometimes groups of college students wander by and look. Government biologists count mud minnows. Community activism ebbs and flows with each new subdivision proposal. Does this add up to stewardship?

A stig is an old English hall or home; a weard is the ward or guardian. Steward is a verb. If we don’t guard the hall of Green Cove Creek, what do we expect for the Salish Sea? The number of institutions dabbling in Green Cove offers an illusion of stewardship. I propose that we fundamentally lack the social infrastructure to be stewards for our watershed. Don’t take this personally; it could be said for any watershed. Anyone in the ecosystem industry can tell stories. Watershed stewardship depends on three practical capabilities that emerge from culture.

First, we must be capable of study. I don’t mean sporadic environmental education lectures, but rather that we have mechanisms by which every citizen can grow to deeply understand their home. This means that we gather and organize evidence and knowledge, and share it with each other constantly. We remember together. We observe the land and synthesize shared knowledge of where we live. This capability cannot be found in our schools nor our governments. We must become again our own carriers of knowledge, but we lack the rituals to do the work.

Next, we must be capable of protecting. All our laws, acts, plans, and restoration projects will not defend the watershed. At this moment, a Puyallup developer wants to build a monocrop of 181 single family homes on an illegal garbage dump located a five-minute drive from 11 toxic waste sites. We struggle to push our city government to negotiate on our behalf.

This is just one of a monotonous series of development proposals grinding away at the last forests and soils of Green Cove Creek; each trying to extract the maximum, and give the least. Do we just wait for the next? Protection is more than effective resistance (and our resistance could be much more effective).

We must enforce good planning at the permit counter. We must enforce clear vision at the ballot box. We need the tools for regenerative development, so we don’t depend on out-of-town profiteers to tell us how to build. Mass migration and climate change are coming. Do we understand what we need to do?

Finally, we must be capable of restoring. We can be allies to beaver clans, infiltrate water, capture carbon in forests and soils, and re-weave the web of life. We need not wait in line for state and federal grants. Restoration can be a community celebration that only requires of us that we understand and take control of our existing shared resources. Restoration is an educational opportunity for our schools. Restoration is employment that builds knowledge, belonging, and wealth. We can restore a watershed with a graduate student, a farmer’s backhoe, and a middle school nursery. What exactly are we waiting for?

In practice, our capabilities to study, protect and restore, will work in synergy. These capabilities will not be given to us. This is a do-it-yourself retrofit that we must earn. We must rebuild the “common hall.” This requires continuous practical effort.

I am doubtful that we should build new institutions. We have plenty of those. What we need is to lean in and shape the ones we have, to become part of a clearer vision and a stronger effort. This requires that we shape how we spend our lives, and nimbly gather in shared work. I hear my professional colleagues say we need more resources to be stewards. I have to laugh. We squander more resources than anywhere on earth! You don’t buy a culture. Everything we need is right here.

Paul Cereghino is a federal ecologist, who spends evenings and weekends working on an Ecosystem Guild—a network of stewards. The Guild studies social systems together, and then designs and builds the capability to study, protect and restore. We are currently cultivating effort in Green Cove Watershed.

End Note—Green Cove Watershed are lands of the Squaxin Indian Tribe ceded under duress, cared for by their ancestors since time before memory (probably at least 400 generations). Stewardship is described by all our relationships. We are in a relationship with the Palouse hills, the floodplains of the Mississippi, the Amazon Basin and the coastal peatlands of Borneo. The proposed Green Cove Park subdivision provides an example of poor stewardship, while students and teachers at Hansen and Marshall schools are exploring in the middle of the watershed, and want to study where they live. We give away our agency, and then our agents work in our name. There are stewards also struggling in those watersheds, and they also need our help. Find maps and documents at Salish Sea Wiki.

What’s it going to take to get governing bodies to listen to ecologists?