Perspective:

Incarcerating more people is not a solution

The Department of Corrections (DOC) is planning to open a new women’s prison at the site of the closed Maple Lane youth detention center in Grand Mound. This prison expansion is opposed by many area residents, and No New Women’s Prison, a group of criminal justice advocates with experiences in Washington prisons that formed in Fall 2019, is trying to stop it.

The proposed DOC project aims to renovate the existing 64 bed juvenile segregation units to provide 128 minimum custody female beds at a cost of $4.38 million, budgeted by the State Legislature. The new prison is being presented as a potential solution to overcrowding at the Washington Corrections Center for Women which has a capacity of 738 inmates. Since 2014, women inmates have been transferred to Yakima County Jail, a site with its own overcrowding problems, allowing DOC to frame the new prison as a “humane” re-entry solution. There is also some secrecy about how many beds are planned. DOC’s website says 128, but a legal services lawyer asserted DOC eventually plans for 700 beds.

Washington DOC’s December 31, 2019 fact card lists an average of 19,160 individuals in its custody, and is operating at 100.3% of capacity. This does not include people housed in county and city jails. The Prison Policy Initiative tracks rates of incarceration throughout the country. It shows the prison population has gone from less than 5,000 to about 18,000 since 1978. The number of women incarcerated in Washington prisons has increased from about 200 in 1978 to 1,449 in 2015, with a sharp increase starting in the mid-80’s. In fact, “Nationwide, women’s state prison populations grew 834% over nearly 40 years—more than double the pace of the growth among men.” In Washington State, the women’s prison population quadrupled in the last 35 years, enough to completely cancel the decline in the men’s prison population. The average cost for incarceration ranges from $90-$150 per day, or $30,000 to $55,000 per year.

Criminal justice advocates point to the documented inequities of mass incarceration on low-income communities and people of color. People with little means cannot afford effective counsel and must rely on the overburdened public defender system and are often the focus of law enforcement. People of color are disproportionately incarcerated and given harsher sentences for the same crimes as their white peers. But women’s incarceration fails women and families in distinct ways.

According to a 2006 report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 73% of women in state prisons had mental health problems. Of these 73%, three-quarters also had substance abuse issues and 68% had a history of physical or sexual abuse. A 2005 study by Northwestern University found that 98% of women in jails had been exposed to trauma during their lifetime.

More than two-thirds of women in state prisons are drug dependent or drug abusers, much of which is driven by a need to self-medicate in response to trauma and victimization. Also, women living in poverty often resort to illegal activities just to survive, especially given the gender inequalities in pay that a majority of women experience. Unfortunately, treatment for women in prison is usually inadequate to address these needs, being the exception rather than the rule. In fact, prisons are more likely to be the site of significant sexual, emotional and physical violence that compounds the suffering of these women and does nothing for public safety.

Another reason for the increase in women’s incarceration is the “tough on crime” policies of the 1980’s and 90’s that were responsible for 40% of the total growth of women in state prisons during that time, a tenfold increase. The “war on Drugs” shifted resources to stricter drug enforcement and other low-level offenses, both of which affected women more. In fact, most incarcerated women were convicted of property or drug crimes—nonviolent offenses.

The Vera Institute of Justice noted that “between 1989 and 2009…the arrest rate for drug possession or use tripled for women—while the arrest rate for men doubled.” Sentences for drug crimes became much longer due to mandatory minimums, “three strikes” laws and conspiracy laws that deliver harsh sentences to even peripheral players in drug offenses. Because women are more likely to engage in low-level, rather than serious offenses, they fell victim to a criminal justice system whose response was incarceration.

Besides the terrible impacts on individual women, the effects on their families are especially troubling. 62% of women in prison are mothers of minor children, and are more likely than fathers to be the primary caretakers of their children. Separating children from their mothers in prisons which often lack face-to-face contact and are often far from home makes visits difficult and expensive. Even worse, if children are placed in foster care, the family can be permanently disrupted.

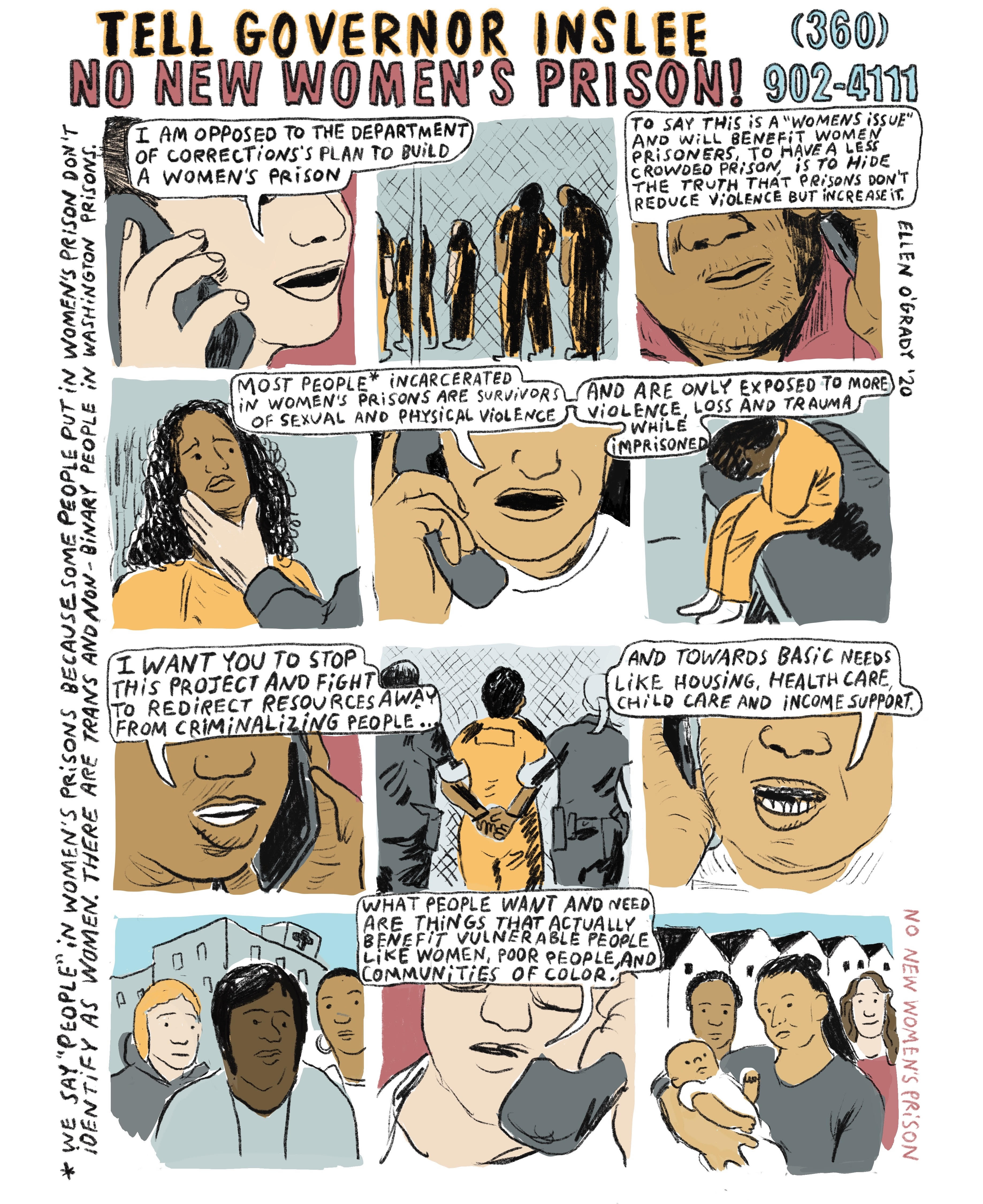

No New Women’s Prison is advocating a different approach. Recognizing the brutality of caging people, they want Washington to stop investing in “racist, sexist, anti-poor, ableist, homophobic, transphobic infrastructure and redirect those resources toward all the things our communities need, like childcare, health care, housing and income support.” Resources would be better spent if directed to the root causes of incarceration—the lack of opportunity, mental health and drug abuse treatment, child care, education and affordable housing. Advocates against mass incarceration, including Angela Davis, concur, pointing to the costly expenditure of scarce state and community resources on prisons that are ineffective at reducing recidivism, rehabilitating inmates, or improving community safety. We see that the COVID pandemic has precipitated the release of many held in prison with no effect on public safety. After all, if prisons reduced crime, the United States would be the safest country in the world, but this is far from true.

For Maple Lane to be converted to a women’s prison, Thurston County was asked to amend the zoning to allow for a correctional facility. In July, 2019, DOC signed a contract with Thurston County to fund an analysis of a draft Development Code Amendment to do just that. The zoning change has been on Thurston County’s radar since the DOC first proposed it in 2015, and was on the “docket” (list of projects they are working on) in 2017, but was never completed.

Over the past several months, No New Women’s Prison has encouraged opponents to contact the County Commission. Sarah Nagy, staff attorney at Columbia Legal Services, wrote in her public comment “…we believe there is an opportunity for the Commission to take a step back and consider the broader implications of this proposal before deciding whether to include it in your agenda… Moreover, we ask that you take time to more closely examine the impacts that the construction of a prison has on the local community and the communities of those who are housed in prisons. In summary, we ask that you choose not to add the DOC zoning request.”

On April 22, County Commissioners rejected the rezone, acknowledging strong opposition from the Rochester community, the facility’s proximity to Rochester schools. They also recognized the strong arguments that activist groups had sent in opposition.

It is not certain what next steps the DOC might take. But we will continue to pursue our goal of ending excessive incarceration of women.

Lea Kronenberg works as a re-entry case manager and instructor for people in prison. She is the daughter of WIP contributing writer Esther Kronenberg.

No New Women’s Prison is also seeking allies to help with communications, outreach, research and connecting with incarcerated people. Contact them via their website NoNewWomensPrison.com, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

To comment on the proposal: Governor Jay Inslee—360-902-4111

Be First to Comment