Sin mujeres, no hay revolución

[Without women, there will be no revolution]

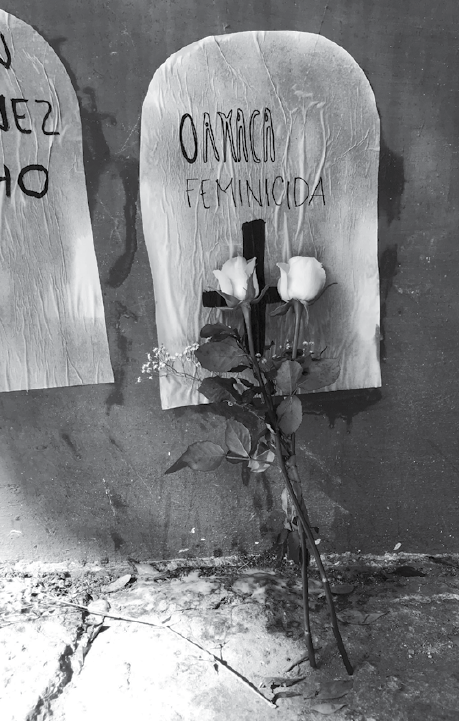

I put a rose against the wall of the graveyard, besides hundreds of others on the altar. Candles illuminated countless names and crosses that spanned the entirety of the wall. Every flower represented a womxn who had either been murdered or was missing, all victims of gender-based violence. Behind me was the roar of thousands of women, muxes1 and children, who had taken to the streets to protest the increasing number of sisters, daughters, and friends who have gone missing, the fear they feel every day to be next, and the indifference shown by the Mexican government. No men were allowed to participate in the march. The percussion of pots and pans banging and the echo of chants vibrated through the pavement. Almost everyone was shielded, with sunglasses, scarves and bandanas hiding faces. A sea of womxn spanned as far as the eye could see.

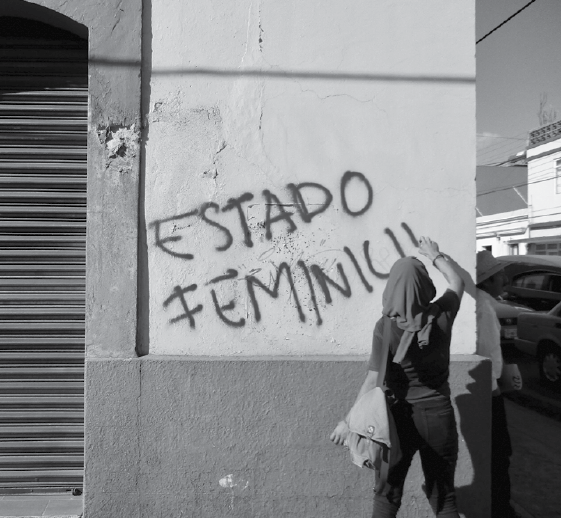

As we moved through our camino with the force and power of a great storm, women in droves pulled out concealed spray paint and stencils to defile the walls of the city with denunciations and cries for awareness. Bank windows were smashed, government vehicles demolished, and every wall we passed was marked with the faces of local men—los violadores. The police dared not attempt to stop the masses. They stood and watched from a distance, some of them seemingly understanding the show of public rage.

Marching through the streets of Oaxaca, Mexico on March 8th for International Women’s Day feels like a lifetime ago. Days before global coronavirus shutdowns, the sweat and tears of others brushed past me in a wave of bodies that flooded the city. In that moment, womxn proved to the state that they hold immense power, and demanded that their pain no longer go unacknowledged. At the time of the march, there had been 24 femicides in Oaxaca and a total of 267 in all of Mexico since the beginning of the year, just a little over two months. With mandatory stay-at-home orders implemented almost immediately following the protest, femicide cases have increased by over 200—bringing the number of women murdered in Mexico in the first quarter of the year to almost twice what it was five years ago.

It is important to note that domestic violence is deeply prevalent in the United States, as well. Long-standing patriarchal structures encourage misogyny in our society, our government and our homes. One in four women in the US suffers severe physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner, and countless others at the hands of bosses, family members or complete strangers.2 Statistics concerning violence against indigenous womxn and the prevalence of impunity for perpetrators are especially disturbing.

In quarantine, women and girls suffering domestic violence have lost their autonomy and freedom of mobility. The support systems that helped them find strength and refuge—even just the ability to talk with someone about their experiences—have all but eroded. Reported cases of domestic child abuse have decreased substantially, with children home from school across the nation. The walls of their homes do not represent safety and security, but a cage that locks them in with their abusers.

Governments around the world have attempted to combat the spread of Covid-19 with confinement and increased police violence, bringing other pandemics to the surface: domestic abuse, economic inequality, racial violence, to name a few. These pandemics of state-sanctioned violence have become so normalized that the spark of collective resistance seems dull.

Even though the candles lit on International Women’s Day have long blown out, the flowers withered and the posters from the march painted over, the collective pain and hopes of thousands of women prevail. The message that together we are all, is as true as it’s ever been. Our collective pain must allow us to stand in solidarity with one another, to fight for the justice and security we so badly need, as thousands of womxn did in Mexico.

Photos by Lindsey Dalthorp, words a collaborative process between Lindsey Dalthorp and Amanda Zavala.

Lindsey Dalthorp, a photographer and writer, splits her time between Olympia and Mexico City. Amanda Zavala, a writer and teacher, works on food security and liberation education. Both are students at The Evergreen State College.

1 non gender-conforming people (Zapotec)

2 National Coalition Against Domestic Violence data

Be First to Comment