WIP READERS READ BOOKS

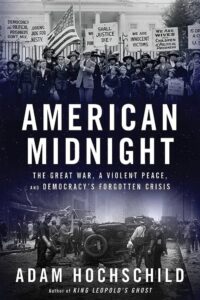

In his detailed history, subtitled The Great War: A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, Adam Hochschild guides the reader through an extensive examination of the turmoil in American society during the period of the Wilson administration before, during and after World War I.

In his detailed history, subtitled The Great War: A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, Adam Hochschild guides the reader through an extensive examination of the turmoil in American society during the period of the Wilson administration before, during and after World War I.

He probes racial conflicts, including the lynching of American servicemen of color upon their return from combat. He details the silencing of contrary viewpoints in the run-up to the war—a war praised by economic interests who were already profiting from sales of ammunition and supplies to both sides of the confrontation.

According to Hochschild, “by the time the United States entered the war, the British government was spending 40 percent of its military budget in America.” He examines labor activism through the rise of the International Workers of the World (IWW) here at home (including armed conflict in Centralia), as well as the Communist Revolution in Russia. Hochschild chronicles the growth of the federal surveillance state, with the earliest career endeavors of one J. Edgar Hoover.

Racial tension, labor struggles, capitalist-driven wars, government spying on perceived dissidents at home. If these things signal midnight for America, one might well ask whether the clock has moved much at all over the last 100 years.

What Hochschild has done, however, is to shine a search light onto this particular period in order to illuminate many of the great voids in our standard American history textbooks. This period is typically presented as the story of how “Woodrow Wilson sought to create the League of Nations after the United States helped the Allies to win the First World War.”

Instead Hochschild found the “story of how a war supposedly fought to make the world safe for democracy became the excuse for a war against democracy at home.”

Here are a few instances whose echo we might hear today:

“A Minnesota pastor was tarred and feathered because people overheard him praying in German with a dying woman.”

“The Post Office asked the ‘cooperation of librarians in the matter of destroying all copies in their libraries, of books that have been declared unmailable.”

“When young Eugene O’Neill took his typewriter to the beach on Cape Cod, the sun reflecting off the metal made someone think the playwright was sending coded signals to German ships or submarines. He was arrested at gunpoint.”

“Congressman Albert Johnson (of Washington State) claimed wildly that ‘aliens were being smuggled across the Mexican border at the rate of 100 a day, a large part of them being Russian Reds who had reached Mexico in Japanese vessels.’”

“On Memorial Day 1927, a march of some 1,000 Klansmen through the New York City borough of Queens turned into a brawl with the police. Several people wearing Klan hoods were arrested, one of them a young real estate developer named Fred Trump.” (Quotations from pages 7, 68, 177, 286, 356)

How little the clock has advanced! Rather than the old tired cliche of history repeating itself, perhaps there is something about our culture and system of governance which keeps our democracy frozen in time at midnight.

The current bemoaning by one party of the weaponization of the federal government, as if that were something new, speaks more to the practice by both major parties of characterizing their actions as righteous for the country–while the other side claims overreach that is a direct threat to their freedom and democracy itself. If we’re at midnight in America again, it’s hard to think of a period that could be labeled high noon…

While Hochschild does look at many of these events with subtle nods and comparisons to the more recent political environment, he keeps his focus on the period in question and delivers an expansive and highly readable history.

I recommend the book to anyone who thinks we are in our darkest hour. I hope we are inching toward the early light of a new day in our democracy, but after finishing the book, I am concerned that we might not make it that far.

Tim Coley is a lieutenant with the Washington State Patrol, where he has worked since 2000. His true passion is reading and writing —when not walking with his dog Adele and husband Jason.

Be First to Comment