In 2015 commissioners at the Port of Olympia adopted a set of financial measures to set goals and track the performance to those goals. If ever the Port of Olympia is going to achieve fiscal soundness, this is sorely needed. The goals were aspirational in that they strove to improve operational performance. For example, one goal was to improve the return on operating revenue from -25% to +5%.

The positive aspect was that it highlighted a need for improved performance that was tied into reference points in the port’s formal accounting. The weakness was that there was no solid business plan to achieve this turn-around.

The port’s 2019 Budget shows a planned operating margin of -15.4% against the goal of +5%. Rather than amending the goals to more realistic targets (e.g. return on operating revenue of -5%), port staff is recommending junking the existing goals and replacing them with some arcane measures that are not expressed in terms compatible with the formal accounting. This approach is problematic.

Before adopting new financial measures, our port commissioners should consider several factors:

- Will the measures be clear—or so confused or opaque as to be difficult to perceive or understand?

- Will they function as a microscope to gain deeper insight into empirical realities—or as a kaleidoscope presenting pretty images detached from outside realities?

- Will they provide real financial analysis—or represent a return to the magical thinking that has caused the port’s on-going financial woes (e.g. irrational capital investments)?

- Will the measures comport in spirit with GAAP accounting and the standards of the State Auditor (e.g. tax receipts are not to be treated as operating revenue)—or become a surreal, Alice-in-Wonderland type of accounting?

How to arrive at a true picture of the port’s financial condition

Over the years, businesses have developed a variety of financial measures that offer them the opportunity to present their financial situation in different ways. Some are designed to look positive (for the investor), some to look negative (for the tax man) and some actually present an accurate picture. Three are relevant here: 1) EBITDA; 2) Return on Total Revenue; and 3) Income (loss) before Tax Levy

(1) EBITDA (Operating) Margin: refers to Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization. Operating income divided by operating revenue defines how efficient the Port is at measuring expenses compared to revenues. Essentially, it’s a way to evaluate performance without factoring in financing decisions, accounting decisions or tax circumstances.

The last thing that the Port of Olympia needs is more magical thinking in the form of “down the rabbit hole” accounting

A management focus on improving cash flow through increasing operating revenues and controlling direct operational expenses is appropriate. However, utilizing a measurement that ignores the key factors of depreciation and interest on capital items equates to poor governance. The financial mess at the port is in large measure due to commissioners’ disregarding these key factors both in making investment decisions and in monitoring performance.

At the September 19 work session, port staff showed an exhibit indicating a surprising EBITDA margin of 20% for 2018 while the 2019 Budget would indicate an EBITDA margin of 13.7%.

The 2018 margin was enhanced, it appears, by lower cash expenses. The largest contributor was the reduction of supplies and utility costs at the stormwater facility, probably due to the system being down. However, the port is under orders to bring the facility up to environmental standards. The port staff has not determined the increased costs for the needed improvement but it is likely that they will be large enough to be capitalized. So, depreciation and interest costs for these improvements will not be included in future EBITDA calculations.

Some commissioners discount the importance of depreciation, claiming that it is a non-cash expense. However, the astute investor Warren Buffett does not agree. He notes:” Depreciation is not a non-cash expense; it is a cash expense but you spend it first. It is a delayed recording of a cash expense.”

The capital investment in the mobile crane is a good example of a reduction in actual cash value. The largely idle crane is worth considerably less than its acquisition cost, and has produced virtually no revenue to offset its depreciated value. Since the port has used different depreciation methods (20 yr/10 yr/ per hour), it may be that the port has not even charged off sufficient depreciation to date.

Then there is the matter of ignoring interest costs on capital items. As a public agency, the port can carry bond interest payments as non-operating expenses. But interest payments are real cash outlays and should not be discounted in financial importance. So, to use EBITDA at a public agency to demonstrate great cash flow is a fictive endeavor.

Arguably, Warren Buffett and his longtime partner, Charlie Munger, are the gold standard when it comes to seeing through clever financial gimmicks. A few of their comments on EBITDA are noteworthy:

- Buffett: “It amazes me how widespread the use of EBITDA. People try to dress up financial statements with it.”

- “We won’t buy into companies where someone’s talking about EBITDA. If you look at all companies, and split them into companies that use EBITDA as a metric and those that don’t, I suspect you’ll find a lot more fraud in the former group”

- “Does management think that the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures?”

- Munger—“I think that every time you see the word EBITDA, you should substitute the word ‘bullshit’ earnings.”

Given the port’s record on bad capital investments, it appears that utilizing “tooth fairy accounting” is not a very good idea.

(2) Return on Total Revenue: total income divided by total revenue. This indicates how profitable the Port is compared to its total income.

This proposed financial measure is distressingly problematic. Although it is not formal accounting, it seems to violate the spirit and integrity of responsible accounting. It basically serves as a ruse to convert property taxes into de facto operating revenue.

The following statement is from the Office of the Washington State Auditor:

GAAP governments are not created to generate tax revenues. Taxes are not comparable to charges for services, as they are [the] result of statutory authority only. It does not matter how specific the tax is regarding its use or purpose. Property and other taxes should always be reported as nonoperating revenue in proprietary fund statements.

Taxes are, in general, levied to assist in funding the deficit or net cost of operations and are not received due to proprietary fund operations.

The state auditor draws a bright line between operating revenues and the taxes to fund operating deficits: “Taxes are not comparable to charges for services.” It appears that this proposed financial measure is designed to conflate tax support funds with operating revenue by creating a fictive “Total Revenues.” This creates a distorted financial picture and will mislead the public. It seeks to improve the appearance of operational results through a stealthy maneuver not based on economic/financial reality. The last thing that the Port of Olympia needs is more magical thinking in the form of “down the rabbit hole” accounting.

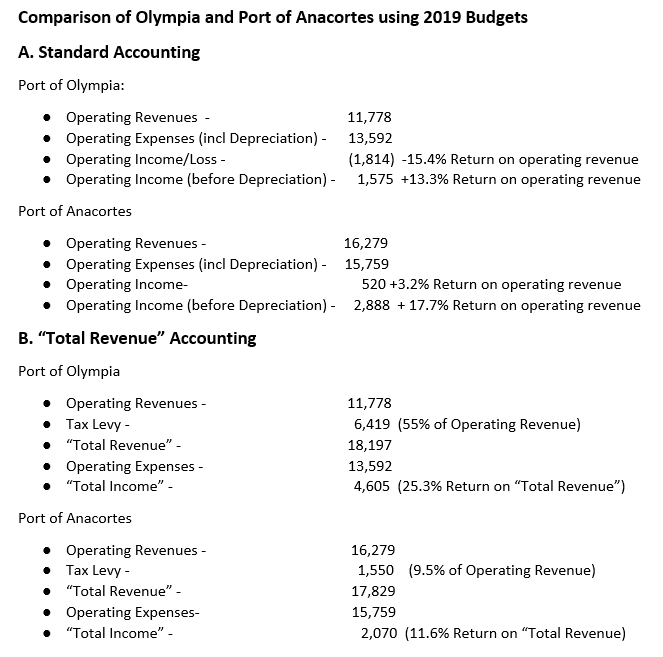

The Port of Olympia and the Port of Anacortes have the same four operating units (airport, marina, marine terminal and real estate) and are somewhat similar in size of operating revenues. So, it is illustrative to compare them financially based on standard accounting and the proposed “total revenue” approach. Under standard accounting, the Port of Olympia shows a return on operating revenue significantly below that of the Port of Anacortes. But use the “total revenue” approach and Olympia comes out well ahead of Anacortes—because 55% of Olympia’s “total revenue” comes from taxes, compared to Anacortes which gets only 9.5% of “total revenue” from its tax levy.

Under the “Total Revenue” approach, increasing the tax levy substantially appears to be the key to operational improvement; witness the 27% increase imposed by the Port of Olympia since 2016. Significantly, the tax levy percentage to operating revenue by the Port of Olympia is about three times that for comparable ports.

Under the “Total Revenue” approach, increasing the tax levy substantially appears to be the key to operational improvement; witness the 27% increase imposed by the Port of Olympia since 2016. Significantly, the tax levy percentage to operating revenue by the Port of Olympia is about three times that for comparable ports.

The Port needs to rely on its Income before Tax Levy approach

I believe that the best governance measurement for managing the Port of Olympia is the Income (loss) before Tax Levy. This is already present in the Management Format Income Statement. Gimmicks like EBITDA and Total Revenue will only perpetuate the mess that the port is in today.

Denis Langhans is a retired corporate executive who holds a PhD in the humanities. He has been observing governance patterns at the port for several years.

Thank you, Denis, for this illuminating description and analysis of the Port.

I hope this will clarify the Port’s accounting methods for all of us.