The King I wish I had known

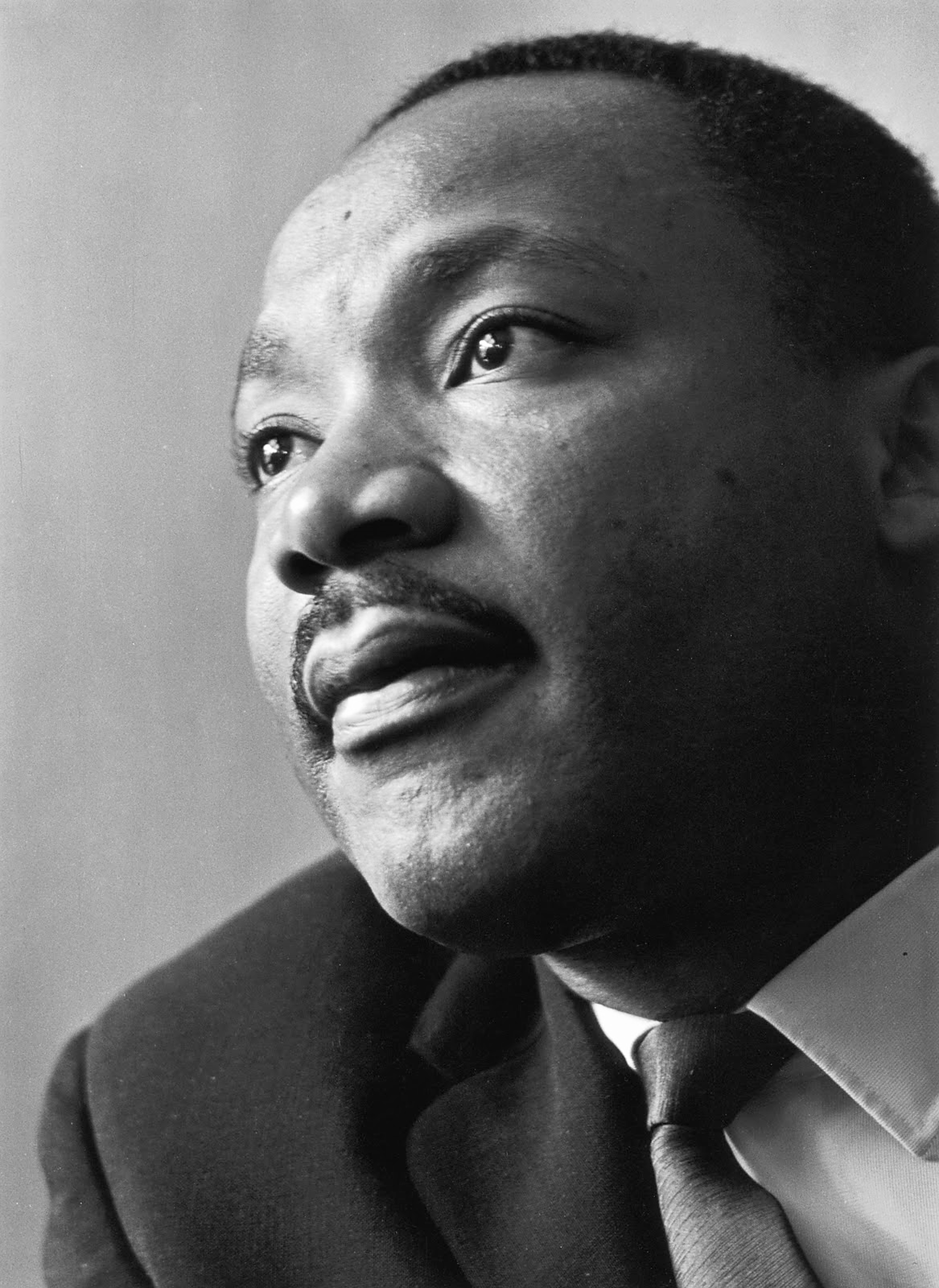

The representation of Martin Luther King Jr. that I grew up with, being only 10 years old when he was murdered, was very similar to the image portrayed in the powerful film, “Selma”, and like most people I know, I grew up reading and discussing the famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

But what happened after Selma, after the 1965 Voting Rights Act passed? How far-reaching were King’s dreams?

Turns out, King’s analysis of what needed to happen next has yet to be fulfilled. As we march through an election season, listening to candidates pitch their visions of the future to the electorate, I strongly recommend that readers pick up the collection of his essays called “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?” The clarity of King’s vision usefully illuminates the issues before us today.

In his introduction to the essays, Vincent Harding suggests that in these later pieces, King was attempting to speak to white allies whose support had begun to diminish as the campaign shifted from working on constitutional rights (like the right to vote) towards fundamental human rights (like the right to adequate housing and income). For instance, in his essay “Where Do We Go From Here” King put it like this: “So far, we have had constitutional backing for most of our demands for change, and this has made our work easier, since we could be sure of legal support from the federal courts. Now we are approaching areas where the voice of the Constitution is not clear. We have left the realm of constitutional rights and we are entering the realm of human rights”

Continuing in a vein that will resonate with readers today, King wrote:

“The Constitution assured the right to vote, but there is no such assurance of the right to adequate housing, or the right to an adequate income. And yet, in a nation which has a gross national product of $750 billion a year, it is morally right to insist that every person have a decent house, an adequate education and enough money to provide basic necessities for one’s family. Achievement of these goals will be a lot more difficult and require much more discipline, understanding, organization and sacrifice.”

Ending “economic strangulation” for all who are poverty-stricken

Just as mass nonviolent action led to constitutional changes, so too, King argued, was mass nonviolent action necessary to move the human rights agenda forward. King acknowledged that many, especially in the North, believed that demonstrations and overt and visible protests could be replaced by the use of legislation along with welfare and anti-poverty programs. King disagreed, arguing that change would only come through mass-action movement. He also argued that the movement for human rights needed to be grounded not only in ending the “economic strangulation” of the Negro, but of other poor people as well:

As we work to get rid of the economic strangulation that we face as a result of poverty, we must not overlook the fact that millions of Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, Indians and Appalachian whites are also poverty-stricken. Any serious war on poverty must of necessity include them. As we work to end the educational stagnation that we face as a result of inadequate segregated schools, we must not be unmindful of the fact, as Dr. James Conant has said, the the whole public school system is using nineteenth-century educational methods in conditions of twentieth century urbanization, and that quality education must be enlarged for all children.

To get where we need to, King argued, we need a “radical restructuring of the architecture of American society.” Such a restructuring depends on overcoming the evils of racism, poverty and militarism, King wrote, and in their place, he wrote, “our economy must become more person-centered than property- and profit-centered.”

How we become responsive to the needs of the poor

According to Harding, in addition to mass action, King’s theory of change depended on two key components: a “coalition of Negroes and liberal whites that will work to make both major parties truly responsive to the needs of the poor” and the recognition that “the larger economic problems confronting the Negro community will only be solved by federal programs involving billions of dollars.”

In this time of election build-up, it’s helpful to re-read King’s farseeing analysis and ask ourselves his questions in a literal way, e.g., where is the multi-racial coalition working to make either or both of the major political parties truly responsive to the needs of the poor? Based on the presidential debates, only those running for the Democratic nomination are responding to the needs of the poor in systemic ways, proposing reforms of the tax code to redistribute wealth and an increase to the minimum wage (though their positions vary). Still, a strong and focused multi-racial coalition focused on economic justice and basic human rights has yet to become the dominant voice in the Democratic party.

King also argued that we need to seek radical change, not minor reforms. As he put it, let us “not think of our movement as one that seeks to integrate the Negro into all the existing values of American society. Let us be those creative dissenters who will call our beloved nation to a higher destiny, to a new plateau of compassion, to a more noble expression of humaneness.” The “revolution” proposed by the Republican candidates does not lead to a more noble expression of our humaneness, and in fact, as many have pointed out, it does just the opposite. That leaves the Democrats, and in the last debate, in and out of the tussles over policy proposals, and questions about what the candidates said about each other, there was a call for a revolution, a reframing of the questions we are asking. And at the heart of that revolution lies the need for campaign finance reform. The need for it would likely not have surprised Dr. King, given earlier efforts to limit people’s participation in elections, nor would the ferocity of the Supreme Court’s protection for wealthy elites in the Citizens United decision.

We need a revolution that begins in the place King landed, where racism must be addressed by making our economy person-centered, rather than profit- or property-centered.

Emily Lardner lives and works in Olympia, Washington.

Be First to Comment