In Ecuador, right now, the wealthiest 2% are engaging in organized protests aimed at undermining a democratically elected government. Some think they intend an illegal seizure of power—a coup d’etat—and the president of Venezuela has called upon leaders in the region to guard against this newest challenge to democratically enacted change.

The nature of the change? As Matt Willgress, writing for the UK publication Morning Star, puts it, what’s happened over the past eight years in Ecuador has been a steady, legislatively enacted shift from corporate regulation of public policy to state-regulated public policy, and now the government, led by President Rafael Correa, is proposing to institute two taxes: an inheritance tax, and a tax on capital gains.

Republicans in Washington oppose capital gains taxes too

Presented with the opportunity to institute a capital gains tax in Washington to address inequities in basic education funding, state Republicans also revolted. Senate Democrats proposed taxing capital gains over $250,000 for individuals or $500,000 for couples at a 7 percent rate. The proposal would have applied to roughly 7,500 people in Washington State, about 0.1 percent of the state’s residents. The House Democratic proposal called for taxing capitals gains over $25,000 for individuals and $50,000 for couples at a 5 percent rate. This proposal would have affected about 32,000 people, roughly 0.5 percent of state residents.

In an op-ed column supporting the Democrats’ capital gains proposals, the Editorial Board of the Seattle Times pointed out that our lack of a capital gains tax makes us an outlier in our region. California has a 13.3 percent capital-gains tax. Oregon has a 9.9 percent capital gains tax. Even Idaho, our nominally less progressive neighboring state, taxes capital gains at a rate of 7.4 percent.

Neither of the Democratic proposals was acceptable to Republicans, who insist that capital gains—the income generated not by work through wages and salaries, but by wealth through dividends and interest—remain untaxed. The likely consequence is that troubling inequities in basic education funding in our state will not be addressed this legislative session, by-stepping the directive of the Washington State Supreme Court.

Why are Washington State Republicans, and the wealthiest 2 percent in Ecuador, so worked up about taxing sources of income other than work?

Redistribution or personal accumulation of wealth: what’s the top priority?

In Ecuador, President Correa asked how a country can be called a democracy if fewer than 2 percent of families own 90 percent of big businesses. How, he asked, in a speech earlier this month, is it really a “meritocracy” when banker and former presidential candidate Guillermo Lasso “earned” 15 million dollars in one year, which is equivalent to 3500 years worth of work for an average worker? How can the work that one person does in a year be worth thirty-five centuries of another person’s work? In what system is that reasonable?

We might ask the same questions about our democratic system. A new report from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) shows the gross bias towards the wealthiest families in the U.S. Currently, the highest income tax bracket and the highest capital gains tax bracket, starts at just over $400,000. The 14,000 tax filers who earned more than $12 million in 2012—the best paid .01 percenters, were taxed at the same rate as those earning $400,000 although they earned 30 times as much. The 1,360 individuals who made more than $62 million were taxed at the same rate too, although they earned 155 times as much as those at the bottom of this high income bracket.

Moreover, Alan Pyke explains in a June 2, 2015 post on Think Progress.org, the richest people in the U.S. became richer in the years between 2003 and 2012, while the middle class got poorer, creating a huge disparity between the .001-percenters who earned at least $62 million, the one-percenters who were making $435,000 or more, and workers paying federal income taxes on earnings as low as $36,055.

The key difference between Ecuador and the U.S. is not the distribution of wealth—in both countries, very small groups of people control most of the wealth. Instead, what makes Ecuador different is that its president is leading the charge to change the tax system as part of a wider plan to implement Article three of the new Ecuadorean Constitution, which reads, “The primary duties of the state are planning national development and eradicating poverty, promoting sustainable development and equitable distribution of resources and wealth in order to bring about Good Living.” As Susanna Ruiz Rodriguez wrote in a policy brief for Oxfam in 2013, “Ecuador is proof that tax systems are above all the result of political will.”

Political will in the U.S.

The strongest political will in our state right now aims to protect the interests of the wealthy at the expense of everyone else, including our state’s Supreme Court. By the time you read this article, the potential government shut-down in our state will likely have been averted, thanks primarily to Democrats’ willingness to “compromise”, which to say, to acquiesce to the Republican’s insistence that the wealthy have the right to benefit from any and all state-supported services while contributing as little as possible. Those who can get the most from our shared public by paying the least have the right to do so. No protest or organized public outcry is expected.

On the other hand, Senator Bernie Sanders is gaining credibility as a contender for the Democrats’ presidential nomination, and he supports taxing income from capital gains at the same rate as we tax income earned from work. Moreover, unlike any other candidate, Sanders is clear about the links between our economic policies, including our tax policies, and pernicious racism and inequality. Rather than getting tangled up in slogans—whether to say that black lives matter, or all lives matter—he explained on NPR’s “It’s All Politics”, “We need a massive jobs program to put black kids to work and white kids to work and Hispanic kids to work. So my point is, is that it’s sometimes easy to say — worry about what phrase you’re going to use. It’s a lot harder to stand up to the billionaire class and say, ‘You know what? You’re going to have to pay some taxes. You can’t get away with putting your money in tax havens, because we need that money to create millions of jobs for black kids, for white kids, for Hispanic kids.'”

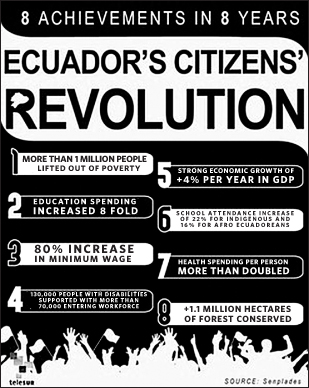

President Rafael Correa is adhering to the values laid out in Ecuador’s new Constitution that put the well-being of people and of nature ahead of corporations. Spending on healthcare and education has doubled since he took office eight years ago, and the percent of people living in extreme poverty has declined from 16.5 percent to less than 8% (Matt Willgress, Morning Star Press, UK). The elites are rebelling, however, and in that rebellion, they are trying to enlist the support of elites in other countries including our’s.

Search U.S. media for “citizens’ revolution in Ecuador” and you will discover how quiet our press is about the profound changes going on just south of us. In the absence of public discussion in this country about the positive changes occurring in that country—“hope at the ballot box”—U.S. official policy towards Ecuador continues to be hostile, so hostile that Correa and other Latin American leaders warned of a potential U.S. backed coup. President Nicolas Maduro, of Venezuala, called on the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) in June to discuss tensions and possible coup plots against the government of Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa (www.teleSURtv.net/english).

Fortunately, the political will of people in the United States appears to be changing. The Occupy Movement helped crystallize a common vocabulary for talking about economic inequality—and the surprising support for Bernie Sanders’ candidacy suggests a clearer focus, perhaps a wider coalition, on the left. Nonetheless, the events occurring in Ecuador right now are instructive: change won’t happen easily. It isn’t easy to organize a citizens’ revolution using electoral processes and policy making, and when it really starts to work, the 2 percent begin fighting back.

Emily Lardner lives in Olympia, where she teaches and writes.

Be First to Comment