I met Cipriano Rios Alegria back in 2014. He was detained and on hunger strike at Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington (NWDC). It’s one of the largest detention centers for immigrants on the West Coast. NWDC has been on my radar since it opened in 2004, but I didn’t set a foot there until February 2014 when I helped organize and participated in a civil disobedience action to stop deportations at the facility. Less than a month later, I met Cipriano.

He and 1200 other people detained at NWDC started a hunger strike calling attention to the inhumane conditions people face there everyday. His family reached out to us, local media outlets reached out to us, and when we finally connected directly with him, he told me: “You are the one who blocked the buses? We need your help.”

I worked with Cipriano for a year; all that time he was detained. The weekend before he was deported I visited him. He told me he was tired of being detained, but we in the outside must never stop—get tired yes, but never stop, until that place, NWDC, is shut down and no more detentions and deportations happen in this state.

Our work hasn’t stopped since he was deported to Mexico. I learned from him, one of the best community organizers, that when you get tired, you get more support, rest and then keep going. I learned from him how to understand the system from the inside, and most importantly that people will always be in resistance, no matter how tired they are.

Since that first and largest hunger strike in the history of U.S. detention centers, more hunger strikes have happened—over a dozen since 2014. This year alone we have seen three more. As I write this, the people detained at NWDC are 3 weeks into another round of hunger strikes and resistance.

Hunger strikers’ demands

Usually, hunger strikers’ demands begin with food quality. Food is basic human nourishment. So why go on hunger strike then? Well, the hunger strikers at NWDC have told me that it’s not hard to stop eating since the food quality is so low. “Not even dogs would eat this food,” a striker told me once. Most importantly, being detained makes it hard for anyone to organize or to be heard. Starting a hunger strike is a powerful action; “Stop eating to be heard,” as Cipriano would say.

The strikers’ demands are divided in two categories: detention conditions and the immigration system. The two are intertwined. The immigration system creates a sea of non-citizens, both documented and undocumented. It works alongside the criminal justice system to criminalize our presence and build the justification for our status, or lack of it, in order to place us in deportation proceedings. Then detention comes into the picture. Detention in the U.S. is a system that profits from the civil incarceration of brown and black human bodies.

This is a summary of the demands we have received from 2014 until today: better food, lower commissary prices, clean clothes, new bedding, medical care, contact visits, minimum wage for work performed, lower bonds, speedy trials, and an end to transfers to other facilities where detainees are far from their lawyers and don’t have access to a law library. The strikers have demanded that those ordered deported be deported quickly and not have to wait for months. They demand an end to retaliation against those engaging in First Amendment activities and an end to the mandate that people stand up when the warden walks into the unit. They demand an end to the separation of families at the border and in the interior, and the release, first, of people with medical conditions, then, of parents with small children. Ultimately, they demand that the facility be shut down and and a stop to all detentions and deportations.

Every set of demands that the strikers give us is a clear road map to shut down the detention center. First, better conditions and humane treatment; second, the end of profiting from captive slave labor; then, a fair process for people to have an opportunity to stay in the country with their families; and finally, releasing people in order of urgency, determined by their health and family conditions.

Those who have attempted to refuse food for a week or more say that the most difficult thing about a hunger strike is being alone. That’s precisely what Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Geo Group, the corporation that owns and runs the detention center, use against people who are detained and who try to organize for human rights. Retaliation is swift and harsh. In the past ICE would wait three days to move people on hunger strike to medical isolation. This year we have seen guards moving people to segregation, or “the hole,” as people detained know it, the same day a strike begins. We saw one case where three people were beaten up by a guard just for joining the strike on the first day of refusing food.

Retaliation also includes transfers to out-of-state facilities, denying family and lawyer visits and denying access to phones, tablets, and the commissary. This time Geo and ICE seem to be repeating the behaviors we saw in 2014. They are sending people to segregation for joining hunger strikes, calling it a “disturbance” and “instigating a group demonstration.” One of the worst forms of retaliation is the cruel threat of force-feeding; this is torture for anyone who has chosen to starve themselves for justice. Geo guards and ICE officers seem to enjoy describing in detail what people will go through if they are force–fed. In these latest rounds of strikes, officials have informed hunger strikers they are ready to file a court order to begin the force-feeding process.

We have lost our fear

Our work is not only to expose these human rights violations, psychological torture and inhumane treatment but also to build political and public pressure. We faced this threat in 2014 and are facing it again this year. We depend on legal support to remind ICE they can’t get an order from a judge without first obtaining one from the Clinical Medical Authority stating that “the detainee’s life or health is at risk.”

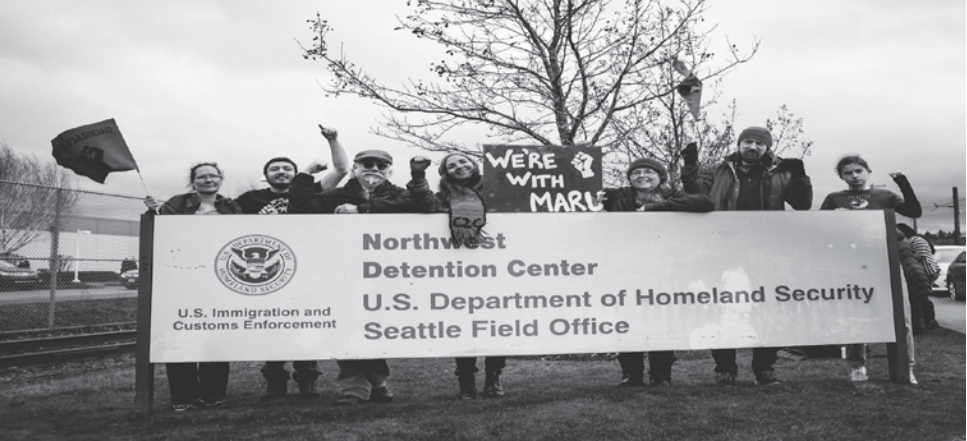

Most importantly our work is to ensure that the voices of detained people are heard through their refusal of food. We know being available and present outside the NWDC is critical to their struggle. They often can’t see us rallying for them, but sometimes they have been able to hear our chants. They believe us when we tell them they are not alone. They believe us because we are still here, more than four years later, answering daily calls from inside, listening to their heart breaking stories. We are outside the detention center in winter, spring, summer and fall. We talk to families–families like ours that want to find someone to listen and offer a hand without asking anything in return. They believe us because we understand the fear and oppression our communities face everyday; we understand that a war was declared against us.

There is one thing we have that others don’t, we have lost our fear. We are ready to fight for all, shoulder to shoulder, next to all the people who are detained, not in front of them.

As Cipriano would say, “What else are they going to do to us? Deport us? We are already in deportation proceedings? What else can they take away from us? They don’t have enough holes in here for all of us.”

For those of us on the outside there are no holes—so what are you waiting for?

Maru Mora Villalpando is an undocumented community organizer with NWDC Resistance, a grassroots volunteer group working to end detentions and deportations in Washington State, and shut down the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma. She is a single mother raising a mature critical thinker and college student who has joined her on several direct actions. She has been targeted by ICE and put in deportation proceedings due to her work.

www.nwdcresistance.org @nwdcresistance