WIP converses with Daniel Einstein of OlyEcosystems about their efforts to rescue the West Side Woods

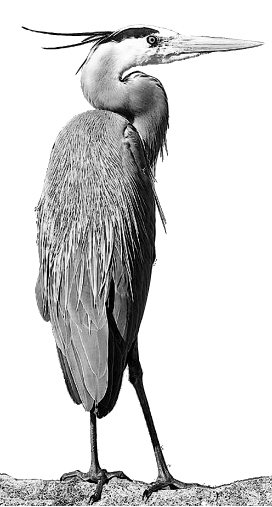

Last summer, Olympia was focused on the West Side neighborhood near the Olympia Food Co-op as it rallied around the heronry at the end of Dickinson Avenue. The sole blue heron nursery within city limits and one of only five remaining in Thurston County, it was threatened by the proposed development of the Wells Townhomes project.

People spoke at city government meetings and many signed an online petition. Letters were written to government officials and The Olympian and interviews were given to local radio stations. It seemed like a vertical uphill battle and then suddenly it was announced in October that Alicia Elliott had purchased the property and the heronry was saved. The Olympian, which had not taken a position until then, printed an editorial praising the purchase.

That one individual with means stepped forward to protect a local animal habitat is a delightful (and extremely important) Olympia twist, but it is not the only interesting aspect of the story.

We’ve been here before

The movement to save the heronry actually started back in late 2007 when Glenn Wells filed his first land use application with the city of Olympia. The local residents responded in opposition with numerous letters to the city and other activities, but they had no effect.

The city issued Wells a permit and in January 2009 he logged a 450 foot driveway through a portion of the heronry. Daniel Einstein, of the Olympia Coalition for Ecosystems Perservation, reported that the driveway was not built on Wells’ property, but on an easement through an adjoining parcel. “The permit applied only to the parcel on which the townhouses were to be developed. It never spoke about the easement that goes right through the heronry. No one from the city ever went on the property to find out if things were done properly. When you look at the closing document it says ‘not inspected.’”

Einstein continues, “Why it didn’t get inspected is hard to say. Until recently, [the city] only had a part-time urban forester. In the 2015 budget, in part due to our advocacy, the city is getting a full-time forester. You cannot not inspect your permits.”

The collapsed housing market in 2008-2009 proved a temporary respite for the rest of the heronry. According to Eintstein, Wells allowed his permits to lapse in 2010.

Walking the dog enlightenment

Early last June, Stephen Bylsma was walking his dog near the heronry when he spotted a sign announcing a May 22 meeting of the Olympia City Site Plan Review Committee regarding the Wells’ townhouse project. As the meeting had already passed Bylsma immediately contacted Steve Herman, a professor emeritus at Evergreen, informing him of the threatened heron colony and asking for advice on how to proceed.

In his email to Herman, Bylsma wrote, “Some friends [have] said that they walked down the trail and there were already workmen cutting down trees at the forest edge. They were informed by a worker that ‘if they don’t like it, they should take it up at the community talk.’ [Ed. note: Federal law prohibits activity near heronries during nesting season—February-August.]

“I am very unaware of the laws and agencies, or how these situations can be managed effectively, and I know well that you have more insight here.”

Bylsma added that he couldn’t understand why the neighborhood wasn’t alarmed about the construction so near the heronry and wondered if it was well known since the sign alerting the community of the project had been posted in an inconspicuous location.

In response, Herman sent out letters to various people and soon meetings were being held.

Responding to the threat

“In the neighborhood we had always been sort of aware of the threat because of a painted sign someone had posted there,” explained Daniel Einstein, “but as time passed concern fell off… When it came to light again last spring, we started having neighborhood meetings.”

“We convinced the [site plan review committee] to hold another meeting, which was on June 22. Sixty-three people showed up.” Einstein explained the meeting was “open to public comment though not officially a meeting and therefore would not be transcribed.”

“The developer was there. There was also a representative from the federal Fish and Wildlife who essentially spoke on behalf of the developer—he was sort of a shill.

“Steve Herman presented a document from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, which called for thousand foot buffers [around the herony] and said, “Have you seen this document?,” to the city staff. And no, they hadn’t. It turned out to be a rather surprising response when you go back and look at the record because there had been ongoing dialog between the state Fish and Wildlife and the Site Plan Review Committee for years.”

When asked by WIP if he thought that the site plan review committee were ready to grant the permit, Einstein replied, “Well, that was our feeling. There had not been any substantive comments from the city until that time. They also produced this draft approval. It showed their intent in my mind. We [would later] read that to the city council and said, “how can we conclude that this is anything but a forgone conclusion?”

An email from the City

In the latter part of July, Cari Hornbein, of the Community Planning and Development Department, sent out an email informing all those concerned with the status of the Wells Townhome project.

Bethany Weidner, another Westside resident, said that the email claimed “as a result of issues raised by citizens, the developer voluntarily hired a biologist to identify ways to mitigate the impact on the herons and then they’ll take that report and talk to Fish and Wildlife about it.”

Weidner interpreted the email as saying “the project is exempt from State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) review because of the code, based mainly on the size of a project or maybe the number of parking spaces. She added, “It, of course, has nothing to do with the environment. So, as the project was not subject to environmental review, the city did not have to have a public hearing on it, and therefore there would not be much opportunity for public comment..

“However, the city decided that they would make the developer announce a public meeting where people could comment. Hence the sign at the end of the dead end road and the meeting that no one attended.”

According to Daniel Einstein, this is when the neighborhood decided to go to the city council.

“We lined up 13-14 people and they went one person after another. We zeroed in on the Comprehensive Plan as this is what the city is so proud of. We read to them whole paragraphs from the then current Plan—sections about the importance of preserving wildlife and species and habitat.”

Unfortunately, the city council would not be useful on this front of the neighborhood’s fight. As stated on the city website, the Olympia city council is similar to a “legislative branch.” It creates policy, but it does not implement policy. That’s the job of the city manager, Steve Hall, who the website compares to the “executive branch.” The Council cannot alter decisions made by the city staff as the council was reminded during the meeting by the city attorney.

About this same time the group discovered that the city’s Critical Areas Ordinance was also a hindrance to their efforts.

Einstein says “Olympia’s Critical Areas Ordinance has some protections for endangered and threatened species such as salmon and pocket gophers—a couple of animals found locally. Yet it really does very little to protect the wildlife we have around us.”

Great blue herons, which are a priority species, are not currently protected though they could be as a priority species. Coincidentally the Critical Areas Ordinance is coming up for review in September 2015. Unfortunately for the heronry, the deadline for review is September 2015, this is too late to protect it from the proposed development.

What action next?

“Shortly after the city council meeting we established the non-profit [Olympia Coalition for Ecosysems Preservation],” related Einstein. “We felt we needed to get organized, we needed some structure.”

Because the group planned to appeal the land use permit, they hired attorneys.

“We realized that West Bay is a tricky area and we were going to get further with lawyers then we were on our own.

“At the same time we were doing outreach,” he continued, “we were looking for what grants we could apply for and we were talking to Alicia.

“Alicia stepped in on her own. I never said ‘buy these’ to her. I never would have asked. I went to see her at West Central Park, the park she is developing[at Harrison and Division] and said, ‘Your group is kind of unique as you hold land and this is what we want to do. I want to get some advice from you.’ I explained the situation and showed her the parcels on the map. She simply said, ‘Well, we should buy these.’ I was overwhelmed with gratitude. Then we started talking about strategy.

Elliott purchased the property that contained the easement as well as another adjacent parcel and Einstein reports relief, “The decision to go ahead and lock up these properties was a transformative one. We would be in a very different place but for that and it has taken a lot of the focus away from legal action for which, I have no doubt, the city is also grateful.

“At the same time Alicia opened up a conversation with the developer about possibly buying his property, but currently his asking price is not practical. He has been open to dialog. What part of that is due to the change in reality and what is due to a change of heart, I don’t know, but he has been open. The easement still exists though. Legally it still exists.

“It is called a reciprocal easement,” Einstein explained. “That means any future subdivisions of those parcels can buy into the utility Wells was going to lay down for a fee, a late-comers fee. There is reason to believe that he was looking at that as a means to finance the utilities’ cost, which is substantial. He would have to put in a road, sewer, sidewalk, everything. By essentially removing that possibility [of added income], it changed the profitability of the property. So he says he is no longer going to go through the easement. That’s over. He’s apparently now looking for access down below.”

Following Alicia Elliott’s decision to purchase the two parcels, the Westside neighbor group became very low-key. Says Einstein, “We didn’t tell anyone. I still had a lot of people coming to me and saying you’ve got to do this, you’ve got to do that. And our petition reads very generic—we’re going to work on this and we value this and come work with us. All the while we were working behind the scenes to purchase the properties. It was hard to keep quiet for a month and a half, but we didn’t want to get in a price war.”

“Land acquisition is really hard-knuckle politics. Land is power. The conversations with the city transformed almost overnight when we had those properties. Suddenly we were stake holders and we had economic heft that we didn’t have before. That shouldn’t be the case.”

Plans for the future

OlyEcoSystems, as the organization is called for short, in addition to applying for grants, is considering the possibility of an agreement with Forterra, formerly the Cascade Land Trust. “They are based in Tacoma,” Einstein shared, “but they preserve lands all over the Pacific Northwest and have experience in urban areas. An example is Mason’s Gulch in Tacoma, which is very similar to our project. We think it may be a good fit and so far the conversations with them have been positive.

“They run their trust as a business, a little bit more than one would expect, but they’re modest. They require some level of buy-in from the city. Some commitment for matching grants, for example, and just political buy-in.

For the long haul

For OlyEcoSystem it’s not just about the heronry. The neighborhood’s vision of saving the ecosystem of West Bay Woods and Schneider Creek includes the West Bay waterfront and shoreline. The great blue heron, the star of their crusade, will lose its heronry without the neighborhood’s efforts, but a lone priority species does not an ecosystem make.

As stated on OlyEcoSystems’ website, “this ecosystem is critical to the survival of locally threatened coho and steelhead salmon, the landlocked sea-going cutthroat trout and sculpin that are trapped in Schneider Creek, the young salmon from outside our area who come to prepare for their long voyage to the open waters of the Pacific Ocean, and to the many shorebirds whose numbers have steadily dwindled. In short, the health of this ecosystem is important for our whole region.”

And the battle to save it will not be short or easy. According to Daniel Einstein “there are $7.5 million dollars of real estate currently for sale on the West Bay shoreline, the West Bay woods, and along Sneider Creek. That’s the magnitude of it. These areas are hugely consequential for the health of Budd Inlet and for the wildlife that’s there and the wildlife that could be there.”

In addition, Einstein pointed out that the West Bay shoreline is one of the community renewal areas [where properties that are eyesores are transformed into productive use]. He claims the County, the Squaxin, and developers are also interested in what is decided. “So it is complicated.”

Einstein believes Olympia’s Comprehensive Plan is important in defining a future people want to have. He also considers it a huge energy drain because it has no force of law if its ideals are not then codified into ordinances. The Comprehensive Plan can say we value wildlife, but if the Critical Areas Ordinance has no provisions in it for wildlife then it doesn’t matter what the Comprehensive Plan says.

The real battle starts now

There are going to be updates of the Storm and Surface Master Plan, the Parks Master Plan, and the Critical Areas Ordinance. These are documents that should draw from the comprehensive plan and codify it into law. It matters what gets written into city ordinance and that’s where the city council needs to be held accountable.

When asked how the community can best support the efforts of OlyEcoSystem, Einstein replied that people should for now pay attention. Over the coming months the city staff will be developing recommended updates to the Critical Areas Ordiance, which will go before the Olympia City Council later this year. It will be then that citizens need to speak out in support of strengthening this ordinance in order to protect what remains of Olympia’s wildlife habitats.

Sylvia Smith, a resident of Thurston County, is an Evergreen alumna and a member of Works In Progress.

For more information about the Olympia Coalition for Ecosystems Protection, go to their website at www.olyecosystems.org.

Be First to Comment