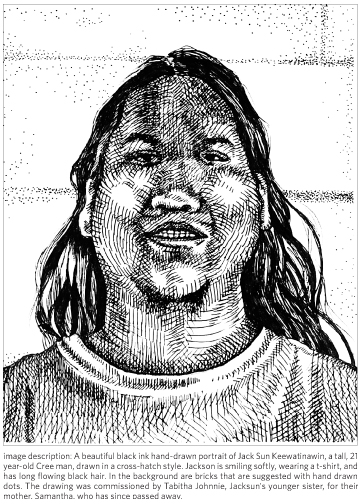

It’s been three years since Montaño Northwind’s brother, Jacksun Keewatinawin, was killed by Seattle police, and he is still reeling from the violence and loss.

“Everything they said on the news about my brother was a complete lie,” says Montaño. “I don’t trust the police, they are racist bullies. Have you seen the Seattle police? In full body armor with assault rifles. Being trained by Israeli military.” He pauses and continues, “One of my kids will be out, and I’ll hear a siren,” he sits straight up and abruptly looks out the window, “I sit up at attention. I don’t want the cops to kill my kids. I don’t want the cops to kill anyone,” says Montaño.

On February 26, 2013, Montaño and Hawk Firstrider each made phone calls to 911 because their brother, Jacksun, was in a mental health crisis at his home and needed help. The police had been called a number of times to help Jacksun get to a hospital to treat flare ups related to schizophrenia and PTSD, in fact Jacksun was even known to call 911 on himself when he was panicked and experiencing hallucinations. On this evening, Montaño and Hawk feared for their brother’s safety, and the safety of their father, Henry Northwind, who Jacksun lived with in Seattle. In previous times of crisis, de-escalation and even hospitalization had proven very helpful in reducing harm. This time, however, when the militarized Seattle police department arrived, they had collectively turned off their dash cams and already committed to the irreversible use of Force. The police themselves admit that within 30 seconds of initial contact with Jacksun, he had been shot and was bleeding out on the ground.

Seattle police officers created their own false narrative about Jacksun’s killing. They quickly demonized and spread their version of what happened in the media, they interrogated and intimidated his family, they intimidated and possibly paid off neighbors and witnesses. Montaño’s home (with his three children) has been watched and photographed by officers in police cars, and both Jacksun’s parents are now dead with no pending Federal wrongful death case.

Henry Northwind and many of his neighbors were the non-police witnesses to Jacksun’s death, and there is said to be no video surveillance. Police told Montaño that was due to a “shift change.”

“My dad was winning a fight with cancer at the time of Jacksun’s death,” Montaño tells me as we sit in his Seattle apartment in February 2016. Aggressive treatment had successfully regenerated healthy liver tissue. The outlook for Henry was stable and hopeful. Then Jacksun was killed. Henry’s health declined and he died just four months later. Montaño views his father’s swift decline in health, and his abrupt death in the hospital, as mysterious, questionable and suspect, and directly related to his brother’s police killing. Henry had been the family’s outspoken leader in the Justice struggle for Jacksun, all the while incredibly grief stricken. “If you ask me, I believe my dad died of a broken heart,” Montaño says.

Henry’s account of what happened was published in the Native press Indian Country Today Media Network in April 2013:

“Henry Northwind was an agonized witness to the horrifying events of that day, and he insists the killing of his son was unjustified. He is a former policeman, and says he is familiar with the proper police protocol for such situations. He says those procedures were not followed.

He says that by the time police arrived in response to the 911 call, his son had calmed down, and that he and Jack were in their front yard. Northwind says he told the police that his son had a knife and a piece of iron. ‘He’s calmed down now, you don’t have to kill him,’ he says he told them. ‘Don’t kill him, please!’

He says the lead officer pushed him aside and said, ‘He’s heavily armed.’

‘I said, ‘Hey don’t kill my son!’ I was in front of them and Jack was [about five feet behind me]. At that time Jack turned around and ran straight back to the house and, in unison these guys moved … and I’d say there were about 15 cops on the curb … They all had shotguns and pistols drawn…[Jack] got to the porch and he turned around and two guys got him in the chest with the Tasers and he just ripped them out and took off again…he had thin, thin, really thin jacket and a real thin, super thin t-shirt, I saw [the Tasers] stick to his [chest] and he went like that”—indicating grabbing both Tasers and pulling them out—“and he just tore them away, and uh, you know that’s at least 50 thousand [volts]! [One policeman] said, ‘He just shook it off like somebody just slapped him!’’

At this point, Northwind’s telling of what happened that night diverges radically from the police account. The police report says Keewatinawin ran and one of the officers pursuing him fell at his feet, and appeared to be vulnerable to an attack. Northwind says this is not true. ‘When Jack ran over here, he slipped—there was no cop that slipped, I swear to God there was no cop, no! Jack was on the ground… and he got up. He (Jack) was on one leg, he was getting up with his hands, and he went like this”—he throws his arms in the air—”and when he did that, they opened fire on him!

‘They said he had something in his hand. There was nothing in his hand, nothing, not a damn thing. That last shot, my knees buckled on me and I said, ‘They killed my son!”

Northwind says a police officer ran up to him and said, ‘What are you doing over here?’ Northwind says he told the policeman, ‘That’s my son you just murdered.’

Northwind claims that officers then put two guns to his head to keep him from running to his son.

He says that when he told one of the officers, ‘That’s my son you just murdered!’ the officer replied, ‘Ugh,’ and ran to the large group of officers. Moments later Northwind says he heard one policeman say, ‘Hey, found it!’ and another officer respond, ‘What?’ ‘An iron bar,’ came the reply. Northwind says he then heard the first officer say, ‘Oh, damn, now at least we have a story.’

‘Right in front of my fucking face they said that!’ Northwind says. ‘One guy said, ‘That’s the father!’ and the other guy says, ‘Oh, shit.’

‘They were wrong, and they were in fear. I could see the fear in this guy’s eyes. I just gave him a tongue-lashing.I asked him, ‘Are you happy? How many more Indians you think you need to kill?’

‘Finally, I just screamed, ‘They killed my baby boy!’”

Read more in the Indian Country Today article “Neighbors dispute police account of shooting of Native man in Seattle”.

When Montaño and Hawk arrived at their father’s home, Montaño described the scene as swarming with police and like a “shark feeding frenzy.” There was confusion and yelling and in a moment of fear, Hawk turned to run away. A police officer pointed a gun at Hawk. Montaño yelled, and another officer glared at him and stepped toward him with his hand on his holstered gun. “Don’t run! He’s gonna kill you!” Montaño screamed. The police kept the two sons from speaking with their father. They were put into a police car, and told “Your dad’s okay. Your brother was shot, but he’s okay.” What they were not told was that the police had a gun to the head of their father, and their brother was dead.

Jacksun’s family were whisked from the scene of his death into separate mirror-lined interrogation rooms at the Seattle police department, where they were questioned for many hours. Montaño says they weren’t allowed to speak to each other and were there until at least 2:30am. Montaño kept asking if they were done. “I have kids to take care of,’” he said. He kept being told that an investigator was on the way, and that these questions were “standard protocol.”

When the “investigator” finally arrived, he asked Montaño all kinds of intrusive questions about Jacksun, about his sexuality, his sexual preference and drugs of choice. “Why are you asking me this?” Montaño asked. “What does this have to do with you killing my brother?” These questions have nothing to do with what happened tonight.” Montaño believes it was during this time that they were building their cover up story, grasping at anything they could to justify the murder of his unarmed brother.

Months after Henry Northwind’s death, Montaño made plans with Jacksun’s mother, Samantha, to go together to scatter Jacksun and Henry’s ashes at the Salmon La Sac area of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. Salmon Le Sac is between the Cle Elum and Cooper Rivers, and a place that Jacksun used to happily dive into near-freezing ice melt. Montaño smiles when he talks about his big and younger brother, a gentle giant he says, and how he would jump right into that near freezing water, all by himself, and was so happy doing it. “This was the place they were both happiest, in the mountains and the wilderness with Mother nature,” said Montaño. At the time the plans were made to spread ashes of their Loved Ones, Samantha was in the fight for Justice for her son, and she was also making great strides in managing her struggle with drug addiction. Montaño says she was doing well, and was living in a sober house. Montaño was looking forward to this time with Samantha, but a month later, she mysteriously died and authorities ruled it “an overdose.” Montaño questions this cause of death. “I believe she was murdered,” he says. “Before she passed she said she was attempting to get legal Justice for Jacksun.”

“Keewatinawin is Cree for ‘the wind that goes North,’” Montaño says. He continues, smiling. “My dad told me that – but he also told me some other things that didn’t translate the way he said,” he says with a laugh.

“Crees are like trees in Canada, we are everywhere. The Cree Nation is one of the largest, but you don’t learn about Cree Nation in history. We were late comers to the plains,” says Montaño. “We came down and settled in Montana. My dad told me that too.”

When asked what Justice looks like for his brother, Montaño says, “Justice for our family would be to have the case reopened. Accountability for the officers involved, an apology for my brother’s wrongful death, and negligent use of force admitted. I want a safe environment for my family to live and grow without worry of killer cops. A wrongful death suit would be the best, but there are no lawyers willing to take the case.”

The Seattle police officers that killed Jacksun Keewatinawin are Michael Spaulding, Stephen Perry and Tyler Speer. Michael Spaulding was the first officer to shoot, the police narrative says that he slipped and fell just before shooting, and that Jacksun raised a weapon (a weapon found by onlookers no where near Jacksun’s body). Montaño says that it was his brother that was on the ground, on his knees, unarmed and with his hands in the air.

On February 26, 2016, the three year angelversary of Jacksun’s death, Seattle police officer Michael Spaulding is currently on paid “administrative leave” for yet another “officer involved shooting.” On February 21, 2016, officer Spaulding shot and killed Black Loved One Che Taylor. Montaño’s family is in solidarity with the family of Che Taylor, and has already reached out to them.

Lisa Ganser is a white Disabled genderqueer artist displaced from San Francisco and now living in Olympia, WA. They are the daughter of a momma named Sam and this is their third story as a writer for POOR Magazine.

This article was originally in POOR Magazine, based in Oakland, CA. The organization is a poor people led/indigenous people led non-profit, grassroots, arts organization dedicated to providing revolutionary media access, arts, education and solutions from youth, adults and elders in poverty across Pachamama (Mother Earth).

Be First to Comment