That vintage illusion called Vari-Vue where you tilt the printed object slightly one way to reveal an image and tilt again to reveal another, that’s how this election season feels to me. The dominant media’s portrayal of a black-and-white binary is far more nuanced; from my vantage point Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Hillary Clinton are two sides of the same coin, occupying a more compressed space on the political spectrum. Remember Bernie Sanders? Jill Stein? Ralph Nader? Shirley Chisholm? Eugene Debs? Victoria Woodhull?

Donald Trump is a person so ill-equipped to be president that those not equipped to make a decision about which candidate among many to elect hear a kindred voice speaking to them, as if Trump, a confirmed narcissist, could relate to anyone other then himself. The world according to Trump is self-reflexive, a convex mirror-mirror-on-the-wall kind of existence, where Trump needs to keep building walls to construct a surface to see all seventy years of his own distorted reflection.

Hillary Clinton’s narrative is differently complex. An ambitious, smart, policy wonk who grew up in a modest Chicago suburban household and attended Wellesley College and Yale Law School, Clinton chose to trade-in the progressive agenda from her early college and career days to enter the White House as First Lady and embark on a life of hardball, centrist politics. Gender seemed to necessitate this choice as our country’s long patriarchal history of icing out aspiring female presidential candidates from any party demonstrates, well after numerous countries around the world have broken the tyranny of sexist exclusion. Clinton’s numerous trade-offs may find her inaugurated in January as the first woman president in United States’ history, but at what cost to her younger self’s integrity? At sixty-eight years, whom does she see when she looks in the mirror now?

So what do the two-party system’s annointed 2016 presidential candidates, who the mainstream media deem as polarizing the electorate, have to do with poetry?

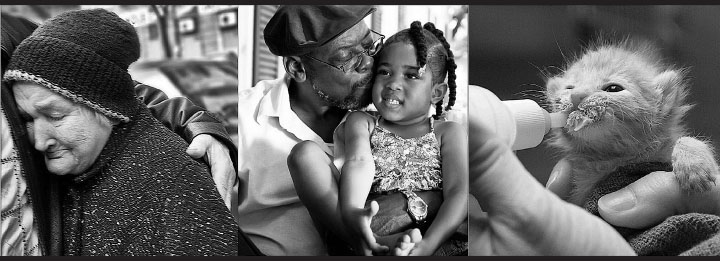

In his May, 2008 talk “Poetry, Love, and Mercy” as The Judith Lee Stronach Memorial Lecturer on the Teaching of Poetry at the University of California-Berkeley, Carl Phillips opened the evening with a reading of an untitled Stronach poem that he believed spoke to “the incongruities of human vision, where compassion, anger, and grief co-exist . . . [and where] the lyric poem is always at some level a testimony at once to a love for the world we must lose, and to the fact of loss itself. And how, in the tension between love and loss that the poem both enacts and makes a space for, there’s a particular resonance that I’ll call mercy, wherein we experience incongruously a bittersweet form of joy in what remains disturbing.” Phillips, a celebrated, award-winning poet whose 2009 collection Speak Low was a finalist for the National Book Award knows something about the confluence of love and loss, both personal and historical, as an African-American, gay poet born before Stonewall.

I, too, know something about this confluence as a member of the LGBTQ community. I began this summer writing about the Pulse nightclub massacre in my poem “Requiem for Orlando,” an early version of which appeared in July’s issue as “Requiem for a Pulse” and at the end of the summer was published in a special memorial issue in Glass: A Poetry Journal. The process of writing and rewriting, then posting recordings of each successive draft on my Facebook page from such diverse locations as outside of Jake’s in Olympia, my front yard, the Rainbow Center in Tacoma, and the Lusitania Peace Memorial in Cobh, Ireland, helped me process publicly the complexities of love and loss that I was feeling at the time. And continue to.

The U.S. Government now exists to manufacture crises, whether a perpetual state of war in parts of the world where too many Americans have no frame of reference and therefore little capacity to hold empathy for its people, or the war on terror in our own country that Trump and Clinton are campaigning on to save the country from the other candidate.

I return to my first article in May where I shared Muriel Rukeyser’s wisdom that “[i]n times of crises, we summon up our strength.” Rukeyser further suggested that poetry helps us steady ourselves against Robert Frost’s “momentary stay against confusion.” In my world, poetry now must take on the added burden of helping me steady myself again the perpetual State of the Union’s manufactured distractions to keep my mind off the things in my world that matter. In this election cyclone of hateful rhetoric that I anticipate will continue its hideous crescendo, cresting like a record-breaking rise of flood water when too few of us will elect to vote for the lesser of two manufactured choices, I am choosing to write. +

Mercy, Nebraska

The distractions manufactured

to keep my mind off

the things in my world that matter

like the precise historical moment

I find myself in when returning

from a prairie road trip and learn

that I love her. And it happens like this:

she maneuvers my car down

the slope of her driveway, pulls up

the parking brake, exits

to unload her luggage.

I dislodge from passenger

to driver’s seat. And for the first time

in many luxurious days, she doesn’t want me

to exit the car with her and stay.

In the awkward rear-view mirror,

I try not to bear witness to her

disappearing inside her house.

I back out onto the main road,

watching for traffic alone, without

the safety net of shared navigation.

The tug of gravel on the wheels

confirms what I am leaving behind.

And just yards from her house,

my foot continues to press against

the accelerator, moving myself away

in the exact moment I hear the new

silence of smooth pavement

and detect a pebble in my shoe,

the irritation telling its truth

under my foot as I hear

someone under my breath

say I miss her, even though

I know I will see her tomorrow.

And that day now cannot come

fast enough. So I press down

harder, plowing my car filled

with absence toward the city, trying

to keep my eyes distracted,

grant some mercy

to the bewildered

rear-view mirror.

If your inclination in these times of distracted election confusion is not to write your own poetry, then read, even a little. Walk, run, bike, or drive your car to one of our local bookstores or libraries and find a momentary stay in a book of poems. Pick up Carl Phillips’ Speak Low, Elizabeth Bishop’s Questions of Travel, Adrienne Rich’s The Dream of a Common Language, or one of Olympia’s exceptional poets, Lucia Perillo, Linda Strever, Tim Kelly, Gail Tremblay, Lorna Dee Cervantes, Don Freas, or Jeanne Lohmann. In between the lines of the poets that traverse the roads of love and loss, remind yourself that mercy is the best antidote to the ravenous rhetoric these times continue to produce, and poetry always offers a welcome home.

Sandra Yannone is a poet, educator, and antique dealer in Olympia. She is a Member of the Faculty and Director of the Writing Center at The Evergreen State College.

Be First to Comment