The system and its discontents

If you don’t agree with the present state of things, there are basically two ways to deal with it: you try to reform it, or you try to abolish it. Both points of view share the conception that things (political institutions, economic systems, etc.) are man-made and therefore, can be “man/person changed”.

The first path, at its best, believes in the possibility of improving society using the political tools within the system, generally conceived as the tools of democracy. This position would support what is known as liberal or progressive measures at local, state, or federal levels. Implicitly, this position conceives of democracy as a thing in itself, a state of being, a noun without adjectives.

For the second path, it is impossible to understand democracy by itself. Democracy necessarily comes holding hands with an adjective or a qualifier tying this form of government to a specific organization of the economy in a specific historical time. This makes it possible to distinguish for example, the differences between classical Greek Democracy; the American democracy of 1790 when the nation was yet to be a fully developed capitalist country (shoemakers were the first trade union of the time), and territorial expansion was as yet an unspoken dream among the founding fathers; and current day American democracy, in which the country has become a highly developed post-industrial global capitalist economy with growing internal inequality, a strong military presence around the world, and a centralized, un-scrutinized, all inclusive state apparatus of surveillance of its own citizens and foreign nations alike.

For the second position it is important when defining democracy to keep in mind the wellbeing and interests of the people, making sure that the concept of democracy is not used to cloak the political and economic interests of a given class and to push back into an ever distant future anti-capitalist transformations. For a good example of sharp policy differences developed inside current day American democracy see Robert Reich’s account of The War on the Poor and Working Families on youtube.com.

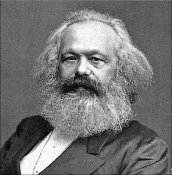

The second position does not ignore the importance of progressive democratic transformations, but is constantly looking for ways to enhance and elevate these transformations to a radical level. The second position does not accept the limits for change imposed by the main beneficiaries of democracy defined without adjectives. This second position is the position of Marxism.

The foretold death of Marxism and the critique of capital

No other political theory has received as many death certificates as Marxism. Sepulchral capitalists, as we mention somewhere else, have shown particular diligence writing most of these certificates. But the death of Marxism, as Terry Eagleton says in his book Why Marx Was Right, “would be music to ears of Marxists everywhere. They could pack in their marching, and picketing, return to the bosom of their grieving families and enjoy an evening at home instead of another tedious committee meeting.” Marxists could stop being Marxists because the job has been done.

Ironically, what has insured the survival of Marxism has been the survival of capitalism. Not in a symbiotic fashion, but because the essence of Marxism is its critical discourse regarding a specific period of time in human history, the one dominated by capitalist production. In Marx’s Capital, A Critic of Political Economy, what he does is not to propose an alternative model to capitalism, but to scrutinize the inconsistences of capitalism and demystify its assumptions. In the words of R.L. Heilbroner in Marxism for and Against, what makes Marx “inescapable” is that he “did not try to find how capitalism works, but to learn what capitalism is.” Marx’s findings, particularly regarding the questionable relations between labor and capital and their detrimental impact on a person’s sense of self, their creative potential, and the right to live in an egalitarian society, is what makes Marxism still relevant.

The revolution—a two step dance

Mistakenly, Marxism is perceived to be alive only when there are clear signals of revolutionary upheaval or social unrest. This is what we know as the revolutionary ethos. In the US the last expression of this was the Occupy movement. Occupy’s expression of the revolutionary ethos was preceded by the great movements of the 60’s and 70’s i.e. the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta’s work with the National Farm Workers Association, The Black Panthers, Students for a Democratic Society, the counter-culture hippie movement, etc.

For the Latin American philosopher Bolivar Echeverria, the revolutionary potential of Marxism—presenting the possibility of a revolution—exists not only when a romanticized revolutionary ethos is popular among the masses, but always—as long as capitalism is alive. The Marxist critique of capitalism keeps alive the concept of the revolution regardless of the status of the “revolutionary ethos.” Marxism offers an ongoing radical questioning of what exists in order to make things better, a line of questioning that can be engaged at any given moment by anyone, anywhere.

Change, within the quotidian of capitalist democracy

Periodically—even with all the above-mentioned constraints—we are given the possibility, or rather, we the people have made possible the potential for exercising certain civic rights, such as voting, supporting bills, and other social actions that will impact our lives. These measures (from electing a new president, to supporting an increase in the minimum wage, etc.) have to be examined specifically, with acute political lenses. We must determine whether—and how—even as we work to support the specific measures, we risk becoming entangled in an ideological trap, our wider aspirations frozen to whatever limit is allowed by a democracy without adjectives. Equally important, as new measures bubble up or are proposed, we need to notice whether—and where—they offer the possibility to raise popular causes to levels of true radical change.

Enrique Quintero, a political activist in Latin America during the 70’s, taught ESL and Second Language Acquisition in the Anchorage School District, and Spanish at the University of Alaska Anchorage. He currently lives and writes in Olympia.

Be First to Comment