Governor Jay Inslee just announced his intention to increase the official estimate for how much fish we can safely eat in Washington, from 6.3 grams per day (about the size of a Ritz cracker) to 175 grams per day (about 6 ounces). This decision about how much fish we eat will determine how clean the water in which the fish swim needs to be. The more fish we collectively eat, the cleaner the water needs to be.

The Clean Water Act of 1972 set limits on the amount of mercury that can be in public waterways. The mercury limit is based on estimated rates of fish consumption, because mercury accumulates in the tissues of carnivorous fish. In the 1980s, using information gleaned from national surveys, the EPA set a fish consumption rate of 6.3 grams per day. In 2000, the EPA increased the rate to 17.5 grams per day. The higher the estimated fish consumption rate, the cleaner the water needs to be. Likewise, maintaining a lower fish consumption rate leads to lower standards for water quality.

Pressuring Businesses and Municipalities

Raising Washington’s fish consumption rate (FCR) puts pressure on industry and municipalities to reduce the discharge of pollutants that find their way into our waterways and it calls into question certain agricultural practices. Increasing the FCR also puts pressure on the state to reduce storm water runoff.

Preventing pollution from storm water runoff is the Puget Sound Partnership’s number one strategy for helping restore the health of the Sound (http://www.psp.wa.gov/action_agenda_center.php). It’s also a huge challenge. Storm water is essentially rainwater that can’t sink into the ground. When rain falls on hard surfaces, like roads or parking lots or roof-tops, it picks up whatever contaminants are there, and runs downhill, into storm drains or into streams or rivers, or soaking into whatever low spot is permeable. It brings along whatever it has washed along in its path, including pesticides and toxins. Reducing storm water pollution calls for a diverse set of strategies effecting zoning and development, transportation, and industry, all of which are hot buttons for the “get government off our backs” folks.

Pushing for more stringent storm water regulations incites the wrath of those invested in private property rights and the right to profit (at everyone else’s expense). Increasing the FCR does the same, with an additional overtone of racism.

Some people eat more fish…

In 2011, Oregon raised its FCR to 175 grams/day, the level that Inslee is proposing, to reflect the diets of people from the Umatilla tribe, Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and avid anglers (Sarah Jane Keller, High bCountry News). According to Catherine O’Neill, member of the Center for Progressive Reform and Professor of Law at Seattle University, data on fish consumption rates among local tribal populations in Washington have been available for the past 20 years. O’Neill reports that the data has continued to mount, with “recent studies documenting fish intake by Asian-Americans/Pacific Islanders and by other Washington tribes at rates of 236 grams/day, 489 grams/day, and 800 grams/day.”

Do Asian-Americans, Pacific Islanders, members of Washington tribes and others have a right to eat wild fish and stay healthy? That’s one of the questions being addressed in the proposed changes in FCR.

Inslee’s proposal a political compromise

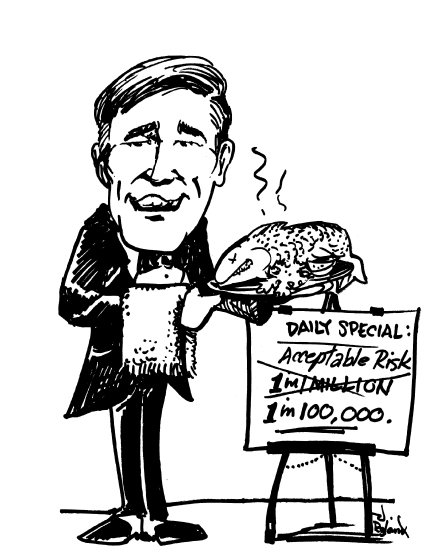

Inslee’s proposal is political. While he proposes that the FCR be increased to reflect the amount of fish people in the state actually eat, he is also proposing that the acceptable rate of cancer associated with eating fish be increased as well. Businesses and some unions support this compromise.

In an April 1, 2014 letter to the governor, re-printed by Investigate West on their website, a self-identified group of “business and municipal leaders” wrote that “establishing human health-based water quality standards on an incremental excess carcinogen risk level of 10e-6 (one in a million) is unacceptable. We anticipate that this risk level, coupled with a high fish consumption rate, will result in largely unattainable ultra-low numeric criteria, unmeasurable incremental health benefits, and predictable economic turmoil.”

As Catherine O’Neill, CPR, writes, the math works out in industries’ favor: “Although Washington’s water quality standards have to date required that people be protected to a level of 1 in a million risk, Inslee has decided that it will now be acceptable to subject people to ten times this risk of cancer, or 1 in 100,000. This move was suggested by industry – The Seattle Times termed it a “canny” suggestion – as a mechanism for offsetting the increase in the FCR that they recognized was likely in the offing, if the standards were to comport with the recent scientific studies of fish intake… What appears to be a significant step forward (an increased FCR) is nearly undermined by a significant step backward (a less protective cancer risk level). Simple math gives the net effect: it is as if the FCR were being nudged upward to just 17.5 grams/day – and our waters therefore only clean enough to support a fish meal every two weeks.”

Oregon raised its FCR without increasing the “acceptable level” of cancer risk. In an article posted by The Stranger on July 2, Ansel Herz quotes a water quality program manager with the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality who said the department was not aware of any business that closed as a result of the rule change. Nor were there job losses. Nonetheless, support for Inslee’s compromise from business and some unions is strong.

Challenge expected from the EPA

A potential challenge may come from the EPA, as shown in a letter from Seattle-based Region 10 director Dennis McLerran to Senator Doug Ericksen (R), chair of the Energy, Environment and Telecommunications Committee. In the letter, McLerran outlines his agency’s opposition to increasing acceptable levels of cancer risk, arguing that to do so would mean “tribes, certain low-income, minority communities and other high fish consuming groups would be provided less protection than they have now.”

McLerran is the same EPA director who announced that the EPA would endorse the analysis of the environmental impact of the Pebble Mine in Alaska, the largest open pit mine ever to be proposed, essentially blocking its development. The Pebble Mine was to be situated right next to the world’s most valuable salmon fishery, Bristol Bay. According to McLerran, the EPA restrictions are designed to “protect the world’s greatest salmon fishery from one of the greatest open pit mines ever conceived.”

Challenging the EPA—a right wing agenda

Those in favor of Inslee’s compromise are arguing that Washington’s elected leaders should send a strong signal to EPA that they will oppose EPA Region 10 actions “to impose unrealistic or unattainable standards that do not meet the unique needs of Washington’s workers, citizens, businesses and local governments. They should also make it clear that they oppose any EPA intervention that attempts to supersede their responsibility to establish Washington’s clean water standards” (Partnership for Washington’s Waters and Workers).

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), an influential right-wing lobbying group funded in part by petrochemical billionaires Charles and David Koch, is also taking on the EPA. According to documents obtained by the Guardian, ALEC has developed a new tactic—seeking out friendly state attorneys and encouraging them to sue the EPA. This is a new twist on their usual strategy, which is to push for anti-climate change and pro-industry bills in state legislatures. (“ALEC has a new tactic it’s using to take down the EPA,” Emily Atkin, ThinkProgress)

Good government, clean water

The right thing to do is follow the lead of Oregon State, by setting fish consumption rates using the best available information, and also by maintaining lower levels of acceptable risks of cancer. To do otherwise, particularly as it is currently being proposed, is disingenuous. One number goes up, the other goes down, and the actual consequence is only a little better than where we are. For an issue that’s been identified as pressing for at least a decade, that’s not very good progress.

Equally important is taking on the argument that principles of environmental justice, which guide the reasoning and the rulings of the EPA’s Seattle-based Region 10 staff. Environmental justice means that we disaggregate data and notice who is actually being effected by current practices, and then respond so that those most at risk from our collective actions are protected.

Washingtonians who eat wild fish have the right to do so—without risking their lives. The right to pollute the waters in which the fish swim—those rights are the ones that need to be challenged.

Emily Lardner teaches at The Evergreen State College and co-directs The Washington Center for Improving Undergraduate Education, a public service center of the college.

An abridged version of this article was previously printed in The Olympian.

Be First to Comment