We know more about the moon and the surface of Mars than we know about the deep ocean. Yet increasing demand for rare metals and valuable minerals could bring industrial-scale prospectors to the sea floor before we understand the nature of the ocean itself, let alone the consequences of ocean mining.

The insatiable extractive economy

Seabed mining (SBM) is an emerging type of mining for minerals and rare earth metals on the ocean floor. SBM could help meet humanity’s insatiable thirst for essential minerals and theoretically power a “greener” economy.

But these mining activities carry a high risk for marine life and our ocean ecosystems, and threaten nearshore waters like the three-mile-wide band of the Pacific Ocean managed by the states of California and Washington. SBM was banned in Oregon state waters in 1991.

The ocean, especially the nearshore ocean, already faces a mixture of stressors: industrialization, climate change, ocean acidification and other forces which will increasingly challenge our ability to understand and co-exist with a healthy ocean. It is increasingly worrisome that there is little left standing between the seabed mining machines and the wonders of the deep ocean.

Threats to Washington’s coastal zones

Washington’s coastal waters are regulated by the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR). State waters include the nearshore area from extreme low tide to three miles offshore. In this zone, there are mineral-rich sands, semi-precious and possibly precious minerals (e.g. gold, titanium), phosphorite and heavy mineral placer deposits. Mineral-rich black sand placer deposits lie along the lower Columbia River, Grays Harbor, and coastal areas between Grays Harbor and Cape Flattery.

While the annual worldwide production of rare earth metals on land currently stands at around 100,000 tons, the deep seafloor is estimated to contain 15 million tons of rare earth oxides. Potential demand for these minerals may drive proposals for SBM. For example, there are concerns that global phosphorus deposits may eventually be depleted. As fertilizer producers perceive the need for new supplies, they may turn their attention to the phosphorus found in coastal zones on the west coast of the United States, including Washington.

Vaccuming the seafloor

Oceanographer Sylvia Earle likens seabed mining to clear cutting forests. Mining is a short-term non-renewable activity. Whether on the earth or sea, once the minerals have been extracted, the resources and the jobs are gone, leaving behind a highly damaged landscape.

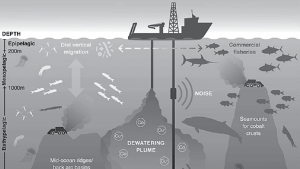

As with land mining, impacts of seabed mining are likely catastrophic. SBM extracts minerals by “vacuuming” the sea floor using heavy, high-tech dredging equipment. Dredged material is piped to a huge barge on the ocean’s surface, where desired materials will be sorted and removed. The unwanted material is discharged back into the water.

A new source of pollution

The effluent released by this process—sediment and toxic metal plumes—is capable of drifting for long distances. Sediment plumes from mining could upset phytoplankton blooms at the sea’s surface, introduce toxic metals into marine food chains, interfere with migratory patterns, and make it difficult for aquatic life to breathe. It has the potential to stir up sediments, block surface sunlight, and destroy aquatic life.

Noise pollution is another consequence of SBM that could change the swimming and schooling behavior of fish, such as tuna. It could cause dolphins and whales to strand themselves. Areas where mining is being pursued represent habitat for turtles, whales and fish, as well as serving as waypoints for migrating species. Some of these areas are already off-limits to deep sea trawler fishing because of documented declines in marine diversity.

A perilous transformation of the planet

Along with environmental groups, representatives from the fishing industry are warning of severe risks to ocean fisheries posed by SBM. Additionally, mining in nearshore areas has the potential to be in direct conflict with recreational activities like beachgoing, whale watching, swimming, paddling and fishing.

SBM could also exacerbate climate change by releasing carbon stored in deep sea sediments. These are known to be a long-term storage system for “blue carbon.”

The combination of these risks presents SBM as one of the largest transformations that humans might enact on the surface of the planet.

The campaign to prohibit seabed mining

There is an active campaign to prohibit seabed mining off the coast of Washington before it can start. Oregon banned seabed mining 30 years ago; Washington and California should enact their own bans. The campaign includes outreach and educational efforts directed at non-profit organizations, state agency officials and lawmakers. Several organizations are circulating a letter for coastal businesses to sign. For anyone who works for or owns a business in Washington or knows someone who does, the letter can be found at

/Biz-Against-Seabed-Mining-WA

Lee First is the Twin Harbors Waterkeeper.

Sources

Greenpeace: Protect the Oceans – In Deep Water – the emerging threat of deep sea mining., http://www.greenpeace.org/international/publication/22578/deep-sea-mining-in-deep-water/

The Oxygen Project http://www.theoxygenproject.com/post/6-things-you-can-do-right-now-to-help-stop-deep-seabed-mining/

Althaus F, Williams A, Schlacher TA, Kloser RJ, Green M.A., Impacts of bottom trawling on deep coral ecosystems of seamounts are long lasting. Marine Ecology Progress Series 397, pp 279-294. 2009.

International Seabed Authority (ISA). Deep Seabed Minerals Contractors – Overview. N.D. June 2019.

Kelly D.S., The Lost City Hydrothermal Field Revisited. Oceanography Vol 20, No.4. 2007.

Rogers A.D., Environmental Change in the Deep Ocean. Annual Review of Environment and Resources Vol 40:1-38. 2017.

Nature, Seabed mining is coming — bringing mineral riches and fears of epic extinctions,August 2019.

Division of Mines and Geology, Marshall T. Huntting, Supervisor, Report of Investigations No. 23, Mineralogy of Black Sands at Grays Harbor, Washington.

More bad news for oceans already in distress.

When will we learn from the indigeous that we are only part of the earth & must respect allother parts for our own sakes.