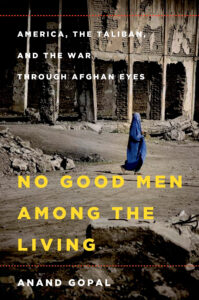

If you’d read Anand Gopal’s 2014 book about Afghanistan and the last three decades of its history, America’s August donnybrook exiting that country would have been unsurprising.

No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban and the War Through Afghan Eyes explains everything about the US occupation and how it avidly pursued its own failure. It wasn’t just the self-serving corruption of George Bush Junior and his henchpeople—it was the failure to serve the Afghan people—our claimed mission. Seen through Afghan eyes, the narrative is wholly different from what we’ve been fed since 2001.

Gopal is a journalist, a New Yorker who was in the city when Al-Qaeda launched the suicide attacks. His interest in the war is explicitly personal. He worked for over a decade in-country, reporting for The Atlantic and Harpers. The book stands apart from other anti-war critics because Gopal sources his material from all kinds of “regular” Afghan people, not just US allies. His informants include men who fought to install the Taliban régime during the 1990s, some commanders who fought against both Taliban and Soviets and non-combatants striving for a modicum of normalcy. Their personal perspectives aren’t always sympathetic, but do consistently describe how events affected Afghan people and their perceptions of Bush Junior’s Crusade.

The most engaging of Gopal’s storytellers is Heela Achekzai. Achekzai is a college-educated woman whose tiny portion of privilege melts away through every shift of régime, including most of the US occupation. It’s Achekzai who provides the author the framework to interpret the historical arc. Gopal wants to know how the US takeover might have benefited her (the kind of person many Americans hoped to benefit). She explains that to understand the present, you have to know the past that led to it.

Heela and her family get by during the Soviet occupation (1979-89) in Kabul, holding down professional jobs. The husband she chose is a worldly partner, grateful for an educated spouse who works. The Soviet times were beneficial overall to metropolitan residents, beefing up education, health and secular rights for women. At the same time, the Soviets were criminally vicious in the bare-subsistence majority of the country, engaging in war against US-funded “warlords.” Outside Kabul, there was no state, just a krazy-quilt of rival brigand gangs, cashing in on opium crops, preying on farmers and shopkeepers, running police as shakedown machines.

The pro-Soviet régime crumbles. The brigands readily form new alliances, survival depending on taking advantage of every opportunity for gain. Kabul falls to rival gangs. Kidnap-for-ransom, protection rackets and rape become the norm.

Heela’s family escapes to the small town of her husband’s origin. There, he caves to custom. She’s subject to “purdah.” Beyond the walls of her house, all her rights vaporize, subject to practices that prevent women from unaccompanied anything, or even letting a stranger hear her voice. She struggles to integrate herself into this very different culture. People finger each other as enemies of one vicious warlord or another. Those fingered die.

This “civil war” lasts until 1996, when the Taliban take over about two-thirds of the country. The Taliban establish a law-and-order society reflecting their fundamentalist religious values. They eliminate crime, end opium growing and the drug business. Ordinary people ally out of a wish for public order.

Heela was now able to work under great stress, mostly in secret, as a midwife. Basic safety improved, but her rights evaporated further. People seem to appreciate the stability, but the Talib elect not to act as a government, only as a terrifying police apparatus. Institutions and infrastructure erode further. Few folk are Taliban adherents. When the US invades and occupies the country, the Taliban pretty much cease to exist, melting away to return to their prior lives.

Achekzai’s family, like most, are hopeful about the invaders, pleased at the opportunity for re-building, looking for the cycle of corruption and violence to end. Kabul mostly flourishes. The international effort pretty much ignores the countryside beyond military bases and roads. Heela, trapped in her rural village, can find only small advantage in her conservative town. She secretly manages a workshop that employs women to make clothes and get paid for it. Her in-laws turn on her and the community expels the alien concept.

The billions of dollars that the US poured into the country renewed cycles of corruption, acquisition, private mercenary militias, police running protection rackets, and a lavishly-funded version of the “civil war” period. By the book’s 2014 publication, it’s evident the US mission has failed (even though the occupation government included Heela as an elected representative).

The new occupiers ended up failing to move rural culture (a multi-generation endeavor). Instead, the US did the lazy thing, dispensing fortunes to many of the same ruthless brigands who made the people welcome the Taliban in 1996.

Gopal’s thesis is built on the narratives of the storytellers. Are interviewees telling Truth in all cases? Perhaps. But when you read Heela’s story and that of ordinary people not privileged to have education; people who shift alliances to try to care for their families, it’s chilling. You see how George Bush Junior’s imperial adventure bypassed the historic French practice of adopting the previous war’s victorious strategy (“fighting the last war”), instead cloning the Soviets’ losing strategy.

It’s an entirely different perspective, painful and worth reading. For a brief but electrifying outline of the US’ failed Afghanistan venture, listen to Anand Gopal’s recent interview with The Intercept: www.tinyurl.com/Gopal-August.

Jeff Angus is a project manager and former US Senate aide specialising in renewable energy.

Be First to Comment