Say the magic word: Affordablelowincomehousing

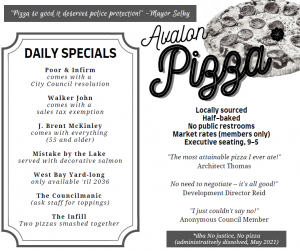

Over the past seven years or so, the city of Olympia has offered a variety of incentives to several developers to invest in “market-rate” apartment buildings downtown. One of the most lucrative offers is an 8-year exemption from property taxes for the building’s owner. The main beneficiary of that incentive has been one developer: Walker John, principal of Urban Olympia LLC.

John has been awarded the tax holiday for six apartment buildings and one “historic” commercial building. Already, the City has given up $6 million dollars in property taxes they would otherwise be collecting from Walker John for the seven buildings his company owns. Another three buildings now under construction will likely be awarded the exemption

All of John’s buildings along with the others enjoying the tax exemption (J Brent McKinley’s Harbor Heights; Aaron Angelo’s Easterly and Shuo Lou’s 123 4th Ave) are all looking for tenants at “market rates.” What once was a downtown with options for very low-income renters is being reinvented as a picturesque location for well-heeled climate refugees.

The City steps in deeper—to pay Walker John directly

In 2016, Olympia’s City Council continued its turn away from “market forces,” and decided to buy a building that had sat empty since it was damaged by a fire in 2004. The City bought the Griswold Office Supply building at 308—4th Avenue from Clifford Lee for $300,000. Lee had paid $257,500 for the building seven years earlier. The City sold the property to Big Rock Capital for $195,000 in 2017, with the bonus that the city would pay for $150,000 worth of environmental remediation. Big Rock’s project never materialized and the property remained with the City.

In the meantime, Walker John had become a preferred downtown developer. In 2020-21, City staff formulated an attractive offer to sell the building with John in mind. The City would give the property to Urban Olympia for $50,000—eating $250,000 of the $300K they had spent (on a property now assessed at $212,000). Taxpayers would also cover demolition needed to prepare the property for John to redevelop —estimated to cost $308,850 (with no ceiling named).

But there was a catch. The Washington State Constitution prohibits cities from giving money, property or credit “to or in aid of any individual, association, company or corporation.” This provision of the Constitution would prohibit the deal as described above.

However, the prohibition doesn’t apply when taxpayer money is to be used “to provide for the necessary support of the poor and infirm.” Here was a way to circumvent the prohibition.

With a requirement for John to offer some units of his future apartment building at rents affordable to “low income” tenants, the City decided it could represent the grant of money as “necessary support for the poor.”

Thus, the Agreement between Walker John and the City states at the outset that the City’s grant of money is permitted under the exception for “necessary support for the poor and infirm.” John will offer 60% of the units in his market rate building as “affordable low income” apartments for a period of 12 years. Assuming a building with 30 units, this would be 18 apartments.

A close reading of the Agreement, however, makes clear that this claim is a mere subterfuge: the deal has nothing for the poor, or even for actual low income working people of Olympia. Under the terms of the Agreement, John could offer all 18 apartments at rents equivalent to market rates and still meet its terms.

How—and why—could this happen?

The answer is in how the Agreement—and the City Code—define “affordable low income.”

Low income? Whoever drafted the Agreement chose the highest possible measure for “low income”—the federal Housing and Urban Development Dept. Area Median Income (AMI). The Agreement says 60% of the apartments “shall be affordable units serving persons with adjusted income of 80% or less of the AMI reported by HUD.” For 2021, the AMI for Thurston County is $90,243. Low income is defined as 80% of that—$72,000.

There is a more realistic calculation of median household income in Olympia that might actually be the basis for affordable rents in Walker John’s new building. The Thurston Regional Planning Commission (TRPC)put the median income for all Olympia households at $59,879 for 2019—a huge contrast with $90,243, even considering that it’s a year later.

According to a study by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLRC), use of the HUD AMI has had the effect in other Washington cities of producing “affordable” units that are even priced above market rates.

Affordable? The Agreement uses Olympia Municipal Code’s definition of “affordable.” Under this definition, whether an apartment is “affordable” isn’t determined by the amount of rent, but by the renter’s income. “Affordable” tells you only that the rent is not more than 30% of the renter’s income. The definition might be good for deciding when someone is “rent-burdened” but it’s meaningless for determining whether a rental rate is “affordable.”

Every market rate apartment downtown qualifies as affordable if the person renting it has wages or income three times the monthly rent. For example, City manager Jay Burney, who signed the Agreement, has an annual income of about $200,000. For him, an apartment priced at $5000 per month meets the definition of “affordable”. The City’s Economic Development Director Mike Reid, who took the lead on the Agreement, has an annual salary of $120,000. For him, rent of $3000 per month would be affordable according to the City code.

“Please don’t throw me in the briar patch”

The Agreement’s terms require John to offer 60% of his apartments to people defined as low income by HUD, and to charge them no more than 30% of their income. Using the HUD adjustment for family size, a family of 3 making $64,960 could be charged a rent of $1624 per month under the terms of John’s Agreement. An individual making $50,560 would pay $1264. If these amounts look little different from downtown rents today—they aren’t. In John’s new Westerman Mills building, a one-bedroom rents for $1425-$1650—about the same or less than that family of three would pay after all of the money the City has granted to John. What’s that old phrase: laughing all the way to the bank?

According to a JLARC study of the 12-year tax exemption, other cities that authorized the exemption have ended up with units priced above market rates.

City Council members who approved the Agreement were presented with a staff report that contained none of this information. Nor did they ask a single question of staff. Saying the magic words “affordable low income housing” was sufficient.

The Walker John Agreement serves neither the poor—nor actual low income Olympians

We’ve seen above that the beneficiary of the Agreement is Walker John. He received a building worth thousands more than he paid for it; he will be able to charge Olympia taxpayers for demolishing existing structures and preparing the ground for redevelopment; he will receive an exemption from property taxes for 12 years; at the end of 12 years, he need only offer 30% of the apartments pursuant to HUD calculations, and at the end of 20 it’s his building to do whatever he likes.

The “necessary support for the poor and infirm”

In 2021 the federal poverty line for an individual was $12,880; for a family of three it was $21,960. These match closely to a definition in an article on poverty in Washington in the Sept. 2019 issue of UW News. A single person under age 65 is considered poor if their total income falls below $13,064. A family with two adults and two children is poor with income below $25,465.

So if an apartment in John’s building were to be affordable for a poor individual under this definition, the rent would be less than $322 a month. For a small family it would have to be less than $550. The day a rent in downtown Olympia qualifies as affordable for a poor person or family is not of interest to any of our decision-makers, nor to real estate developers.

Cost-burdened households and the “working poor”

As noted above, TRPC puts median household income for Thurston County at about $60,000. Note that these are “household” incomes—which includes every earner in the household. That usually means both partners are working. Many are working for wages we would consider below a living wage. In Thurston County, jobs in social service, retail trade and hospitality account for half of the jobs in the top five employment sectors. Annual average wages for those jobs were $55,000, $34,000 and $22,000 respectively in 2019.

For contrast, the median income of individuals employed by the City of Olympia is close to $82,000. (1) Eighteen employees with the title of “Director” make salaries ranging from $131,000 to $161,000. The manager who handles the Home Fund (homeless and affordable housing program) makes $104,000. The City has hired a “Homeless Response Coordinator” for a salary between $78,000 and $95,000.

A summary of Block Grant priorities for Thurston County for 2018—2022 identifies families with two parents and two children as low-income if household earnings are at or below $62,150 per year; very low-income at $38,850 per year, and extremely low-income at or below $25,100 annually. According to the report, more than two-thirds of these households are housing cost-burdened.

There is nothing in the Agreement with Walker John that relates to supporting the “poor and infirm” nor even any hope for people who are officially burdened by their housing costs.

Meanwhile, back at the encampments

The 2020 Thurston County homeless census found that 995 individuals were experiencing homelessness—living unsheltered or in emergency or transitional housing. This is a 24 percent increase over 2019 and is the highest count since the homeless census began in 2006.

Approximately 54% of homeless individuals were unsheltered in 2020 compared to 49% in 2018. “Unsheltered” means living in places not meant for human habitation such as cars, tents, parks, sidewalks, abandoned buildings, or on the street.

Last month, Thurston County committed $1 million to fund case managers to work with encampment residents at Deschutes Parkway, Wheeler Road and Ensign Road, as well as clean up camps and establish codes of conduct. No commitment to actual housing, but careers in homelessness are thriving.

Find this information at http://govsalaries.com/

Bethany Weidner is a long-time resident of Olympia and a close reader of official documents.

Be First to Comment