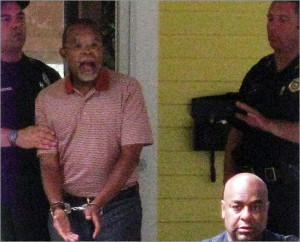

Photo Exhibit #1

Photo Exhibit #2

The first picture features Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African American Research at Harvard University, being arrested for break-in to what was his own home located within a short distance from the school. Meanwhile, the second one shows Dr. Gates and Sgt. James Crowley, the arresting officer, having beer with President Obama at the White House. As you can see from the two photos in question, they reveal different messages. One uncovers a surprised and hostile reaction while the other displays a truce.

Professor Gates’ event took place in July 2009, a few months after Barack Obama took office as President of the United States. The so-called “Beer Summit” did not result in any specific apology by the police, but the photo represented for many Americans the beginning of a new era of race relations, or as the newly elected first black president of the nation put it “I have always believed that what brings us together is stronger than what pulls us apart.” The mute language of photographs seemed to suggest at the time that the two black men from Harvard and Sgt. Crowley—who were joined later by Vice-President Biden for drinks and snacks—were up to something good and significant.

Photo Exhibit # 3

The third picture shows the police using force against people protesting the killing of Michael Brown, an 18- year old unarmed African American man, fatally shot by the police while walking on Canfield Drive, in Ferguson, Missouri.

The shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson took place just a few of months ago. It seems fair to ask ourselves how often police shoot unarmed black men. Jaeah Lee from Mother Jones magazine answers to this question by stating that, “The killing of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri was not an anomaly: as we reported yesterday (8-15-2014), Brown is one of at least four unarmed black men who died at the hands of the police in the last month alone.” Although there is not an official agency in charge of tracking unarmed victims, as Jaeah Lee notes, studies by publications such as Color Lines and the Chicago Reporter conclude that there are a disproportionally high number of black Americans among police shooting victims particularly in cities such as New York, San Diego and Las Vegas.

Bud Light, tear gas, rubber bullets, and the new apartheid

Racism is hard to ignore in America; it has been an integral part of the national character of its dominant groups and allies since the beginning of the nation. But it is also important to scrutinize how nowadays prominent black men deal with racism, and how they are being treated by the powers of the State (in this case represented by Obama himself as the head of State) versus how common black people have been treated in the Ferguson case. There are clear differences between the conciliatory triangle of interracial libation formed by Obama, Gates, and Sgt. Crowley (we can only imagine what are they toasting to in the photo) versus the brutal police response to the legitimate protests in Ferguson. Amnesty International, an organization created fifty years ago to protect the dignity and human rights of those imprisoned or harassed for their beliefs, is generally associated with the investigation of government abuses at hands of third world dictators or “Cold War” era eastern regimes. Yesterday (October 24) Amnesty International released a lengthy report called “On the Streets of America: Human Rights Abuses in Ferguson”, which casts a gloomy light on the conditions of human rights in the nation. The report quotes Navi Pillay, The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, condemning the excessive use of force by the police in Ferguson, and making a “call for the rights of protest to be respected. These scenes are familiar to me and privately I was thinking that there are many parts of the United States where Apartheid is flourishing.”

Apartheid was a shameful term used to describe the harsh conditions of discrimination and racial segregation enforced by the white government of the National party in South Africa, aimed to restrain the rights of association and movement of the majority black population in favor of its white minority.

The vast majority of the protests in Ferguson have been peaceful—as noticed by President Obama himself—and the United States Constitution recognizes—at least in theory—the right of peaceful assembly, freedom of association, and freedom of expression as basic human rights. Nonetheless, according to Amnesty International, the police have responded with direct violent dispersal, tear gassing and other chemical irritants, heavy-duty riot gear, military grade weapons, and rubber bullets, plus the imposition of restrictions on the rights to protest, curfews, and submission to Long Range Acoustic Devises (LRAD). The report of Amnesty international reads not like the report of the social life in an advanced democracy, but like a report describing the conditions in a far away country that can’t be ours.

The same president who promptly sought—and rightly so—to amend the racist wrong doings against Henry Louis Gates, has remained relatively quiet about the abuses experienced by common black people in Ferguson. The Department of Justice has not been vigorous in conducting a transparent investigation into the death of Michael Brown, nor in collecting and publishing the statistics on police shootings in accordance with Violent Crime Control and Violent Act (1994). Nor has The United States Congress acted to pass the End Racial Profiling Act.

Compared to the “beer summit” photo, the report offers us a different kind of photograph of ourselves. It is not nice—it is ugly, shameful and complicated but it is showing a rare ‘selfie’ of who we still are and what needs to change.

Black people’s quest for humanity

In his short story, “Stranger in the Village”, the black writer James Baldwin noticed that the identity of both the white and the black man in America are intertwined. For him, the white American world was trapped without possibilities of escape in the contradiction between their declared moral and civic convictions i.e. The American Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and the exploitative conditions imposed by them via slavery to black people. For Baldwin this condition was inescapable due to the economic necessities of American Capitalism. From Europe (particularly from the British Empire), America also inherited the conviction of white supremacy, which made it impossible for white men “to accept the black man as one of themselves, for to do so was to jeopardize their status as white man”. For Baldwin, it is against the backdrop of capitalism’s necessity of slavery at the beginning of the nation, and the empty and selective discourse of American democracy that the white man seeks to construct his identity, which by its very nature would be fragmented and contradictory.

The Negro identity, on the other hand, is also formed in direct correlation to the economic needs of an expanding white nation (the US) to exploit black men and women through the institution of slavery. Being severed from their past (Africa) and uncertain about the possibilities of taking power from the new masters, Black people survive though their quest for humanity and rights as human beings–a long quest with uneven results as exhibits 1,2, and 3 show in the discrete but telling language of photography.

Enrique Quintero, a political activist in Latin America during the 70’s, taught ESL and Second Language Acquisition in the Anchorage School District, and Spanish at the University of Alaska Anchorage. He currently lives and writes in Olympia.

Be First to Comment