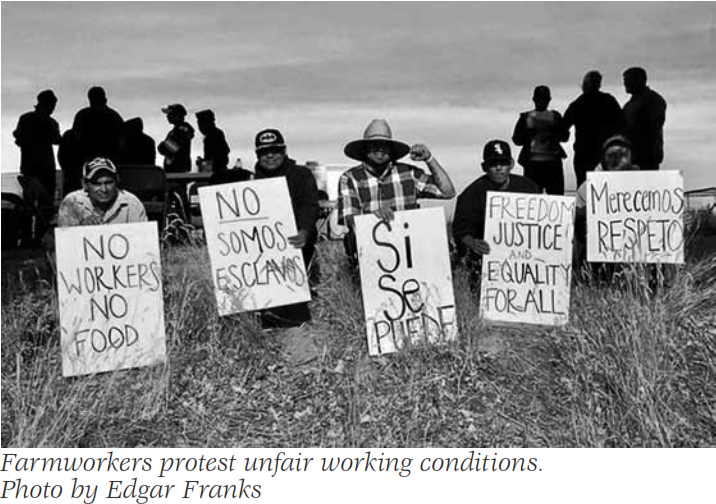

In August 2018, 200 farm workers and supporters began walking at sunrise, north from Lynden, Washington, toward Canada. Chanting and holding banners, the procession passed 14 miles of blueberry fields, finally reaching the border crossing at Sumas. Pausing for protests at the immigrant detention center, it continued on to its objective—the 1500-acre spread of Sarbanand Farms. There, participants staged a tribunal.

The Death of Honesto Silva

“We are here to assign responsibility for the death of Honesto Silva,” announced Rosalinda Guillen, director of Community 2 Community, one of the main organizers. A year before, Silva, an H-2A guest worker brought from Mexico to harvest the farm’s blueberries, collapsed and later died.

Raymond Escobedo, one of Silva’s co-workers [his name was changed to protect his identity], remembered the day he died.

“I could see he wasn’t feeling well, and he asked to leave work. They wouldn’t give him permission, but he went back to the barracks to rest anyway. The supervisor went and got him out, and forced him back to work. Honesto continued to feel bad, and finally had to pay someone to take him to the clinic. When he got to the clinic he was feeling even worse, and they took him to the hospital in Seattle. And so he died.”

Sarbanand denied responsibility for Silva’s death, and claimed a manager had called an ambulance to bring him to the local clinic.

Honesto Silva’s death came amidst workers’ growing anger about their living and working conditions. “From the time we came from Mexico to California we had complaints,” Escobedo explained. “There was never enough to eat, and often the food was bad. Some of the food was actually thrown out. Still, they took money for it out of our checks. They took out money for medical care too, but we never got any. The place they had us stay was unsafe and there were thefts. Some workers in California protested and the company sent them back to Mexico.”

Sarbanand Farms belongs to Munger Brothers, LLC, a family corporation in Delano, California. Since 2006 the company has brought over 600 workers annually from Mexico under the H-2A visa program, to harvest 3000 acres of blueberries in California and Washington. Munger has been called the world’s largest blueberry grower, and is the driving force behind the growers’ cooperative that markets under the Naturipe label. Last year it brought Silva and other H-2A workers to Delano to harvest blueberries and then transferred them to Sarbanand Farms in Washington.

“We thought when we got to Sumas things would get better,” Escobedo recalled. “But it was the same. There still wasn’t enough to eat, and a lot of pressure to work faster, especially when we worked by the hour. They wouldn’t let us work on the piece rate [which would have paid more – ed.]. But what really pushed us to act was what happened to Honesto, when he got sick and there was no help for him.”

Escobedo’s account conflicts with the statement Sarbanand Farms gave following Silva’s death: “it is always our goal to provide them with the best working and living conditions.” Sarbanand called the barracks “state of the art” and described the food as “catered meals at low cost.” Silva himself “received the best medical care and attention possible as soon as his distress came to our attention. Our management team responded immediately.”

The exploitation of guest workers affects all workers

Lynne Dodson, Secretary Treasurer of the Washington State Labor Council, was on the march. She was “heartbroken” to hear about Silva’s death, and even more outraged by what happened next to his fellow workers. When they heard Silva had been taken to the hospital, 70 H-2A workers refused to go into the fields, and demanded to talk with the company about their conditions. They were then fired. Because H-2A regulations require workers to leave the country if they are terminated, firing them effectively meant deporting them.

“Workers may not leave assigned areas without permission of the employer or person in charge, and insubordination is cause for dismissal,” the Sarbanand statement says. “H-2A regulations do not otherwise allow for workers engaging in such concerted activity.”

Dodson responded, “If you get deported for collective activity that’s…saying you have no enforceable labor rights. No right to organize. No right to speak up on the job [or] question working conditions without being deported.” These vulnerabilities threaten both immigrant and resident workers: “Employers bring [H-2A workers] in rather than hiring workers living and working in the area. What’s to stop that from becoming the norm in every industry? Here in a state with almost 20% of the workers organized, we see a farm worker who died and others fired because they tried to organize. If this happens here, imagine what can happen in other states.”

Use of H-2A programs is expanding

Silva was only one of hundreds of workers who die in U.S. fields every year – 417 in 2016 alone. His death stands out, however, because it highlights conditions for H-2A guest workers at a time when growers and their Republican Party allies want to expand the program.

They have the support of President Donald Trump, despite his otherwise sour anti-immigrant rhetoric. At a Michigan rally in February he told supporters, “For the farmers… we have to have strong borders, but we have to let your workers in…guest workers, don’t we agree? We have to have them.”

Companies using the H-2A program must apply to the U.S. Department of Labor, listing the work and living conditions and the wages workers will receive. The company must provide transportation and housing. Workers are given contracts for less than one year, and must leave the country when their work is done. They can only work for the company that contracts them; if they lose that job they must leave immediately.

In 2017 Washington growers received H-2A visas for 18,796 workers—about 12,000 were recruited by WAFLA (formerly the Washington Farm Labor Association, an H-2A labor contractor). “We could be close to 30,000 this year,” said WAFLA president Dan Fazio. Last year about 200,000 H-2A workers were recruited nationwide. This year the number is expected to exceed 230,000.

Over the last two years, attempts to expand H-2A were authored by Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-VA), chair of the House Judiciary Committee, and Rep. Dan Newhouse (R-WA). When their attempts to pass legislation failed, Newhouse inserted a proposal into the budget bill for the Department of Homeland Security that would allow growers to employ H-2A workers without being limited to contracts of less than a year.

Critics charge the change would make replacing current farm workers with H-2A workers more attractive to growers and increase competition for jobs. Instead, Bruce Goldstein, president of Farmworker Justice, argues, “Agricultural employers with year-round jobs should do what any other employer must do to attract and retain workers: improve wages and working conditions.”

Employers of H-2A farm workers target public funds; seek to cut workers’ wages

Another Newhouse effort involved placing a waiver into the 2018 appropriations bill that allows growers, for the first time, to use federal subsidies for farm worker housing to house H-2A workers. H-2A regulations require growers to provide housing. This proposal would give growers access to the very limited public funds for building housing for resident farm workers.

Washington State has also given farm worker housing subsidies to WAFLA and other growers using the H-2A program. This was not the first instance of the state’s favorable treatment to growers and H-2A contractors like WAFLA.

This year, at WAFLA’s instigation, the Employment Security Department (ESD) and U.S. Labor Department tried to slash farm worker wages by up to $6 per hour. ESD is required to survey wages every year to establish a minimum wage for H-2A workers that theoretically won’t undercut the wages of resident farm labor. This year, after ESD published its wage survey, WAFLA appealed to have the piece rate wages removed, leaving only an hourly guarantee.

Last year’s hourly wage was $14.12/hour. In the Washington apple harvest, however, most workers are paid a piece rate that can reach the equivalent of $18-20 hourly. ESD and the Department of Labor agreed with WAFLA to remove the piece rate minimum, effectively lowering harvest wages by as much as $6/hour. WAFLA’s president Dan Fazio boasted, “This is a huge win and saved the apple industry millions.”

In February the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries announced that Honesto Silva had died of natural causes, and the company was not responsible. The department said its investigation found no workplace health and safety violations, although the temperature was over 90 degrees with heavy smoke from forest fires. Yet Nidia Perez, who supervised workers for the H-2A recruiter CSI, had threatened workers, telling them they had to work, “unless they were on their death bed,” or be sent back to Mexico.

Sarbanand Farms was fined $149,800 for not providing required breaks and meal periods, but a judge later cut the penalty in half.

“We reject the idea that Silva’s life was worth $75,000,” Guillen told the tribunal in front of the farm. “No amount of money can pay for the life of a farm worker.”

David Bacon (dbacon@igc.org) is a writer and photojournalist covering labor and migration. His latest book is In the Fields of the North / En los Campos del Norte. This article was edited from a longer version, available at http://prospect.org/article/what-was-life-guest-worker-worth.