A version of this article appeared in The JOLT.

The Port of Olympia owns approximately $500 million in property, according to data received from the County Assessor. But, unlike a normal landlord, it loses money on each of its major commercial business units – the Marine Terminal, Marina, Airport, and rental properties. It subsidizes these losses by raising taxes on every taxpayer who pays property taxes.

Examples of financial mismanagement abound. For example:

1) It bought old cranes, which were only used a few times and then sold for scrap;

2) It bought a new crane, which has almost never been used;

3) It has violated the Clean Water Act numerous times, which cost the Port millions of dollars in litigation, stormwater system development, and penalties;

4) It has violated the Public Records Act numerous times, which cost the Port hundreds of thousands of dollars for refusing to provide public records.

Another example is that the Port of Olympia falsely claims it’s “in the black” financially. But without nearly $4M in property taxes, it actually lost $2.8M in the first half of 2025. The airport and marine terminal also lose money once bond interest on associated debt is counted.

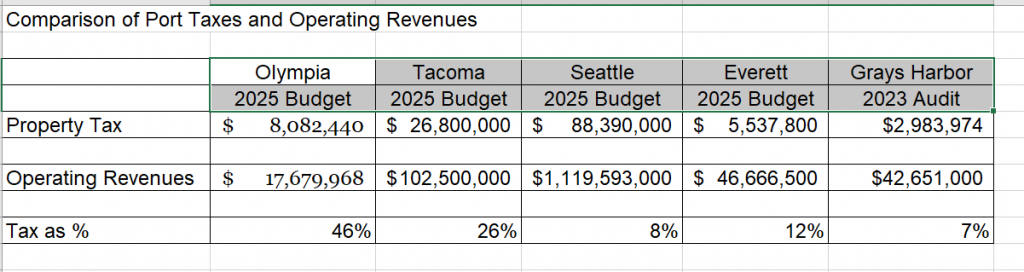

Other ports use taxes too, but the Port of Olympia leans on property taxes more and hides the losses. It gets $8M a year in local taxes. That is an amount equal to 46% of the Port’s operating revenue from all sources –revenue that is paid by Weyerhaeuser, by people who rent slips at the marina, and by people who use the airport or rent hangar space there.

The $8M a year that the Port gets from local property owners isn’t free—it’s our money. The Port is using our money to cover bad finances. We deserve honest books and accountability. This is why voters need to elect candidates this November who plan to make changes, not support business as usual. Voters need to elect Krag Unsoeld and Jerry Toompas to the Port Commission.

Unusually heavy dependence on property taxes

If one compares the financials of the Port of Olympia to those of the ports of Tacoma, Seattle, Everett, and Grays Harbor, one can see just how unusual the Port of Olympia is. The amount of taxes it uses to prop up its budget is almost half its operating revenue, at 46 percent. Compare that to only 26 percent for the Port of Tacoma, 8 percent for the Port of Seattle, 12 percent for the Port of Everett, and 7 percent for the Port of Grays Harbor. The Port of Olympia is two to six times more dependent on our property taxes than these other port districts are.

Hiding debt

The Port generally uses property taxes to pay off its debt rather than to fund daily operations. But the Port’s quarterly financial statement hides this debt from the public and fails to assign the interest on bonds to the different business units for which the debt is incurred.

According to the State Auditor’s Office’s analysis of financial statements from December 31, 2023, the Port owes about $30 million in long-term debt. It pays roughly $4.6 million each year to cover it, and of that amount, about $1.1 to $1.6 million is interest and the rest is principal.

But you wouldn’t know about all that debt by just looking at the Port’s financial statement. The first page of the Port’s June 30, 2025, financial statement (available here) shows the Port in the black, with an “Increase in Financial Position” of $1.2 million. But look just above that, and you will see that the Port included $3.98 million of property taxes from residents in reaching that “bottom line.” Without our property taxes, the Port lost $2.8 million in the first six months.

Then, if you go to the Airport and Marine Terminal pages of the financial report (pages 2 and 37) the Port shows these two operations with $103,000 of operating income for the airport, and an operating loss of ($184,000) for the Marine Terminal. But these figures do not include the $400,000 interest on bonds, most of which is attributable to the Marine Terminal and Airport. When that is included, both operations are losing money.

Residents have asked the Port for several years to show the interest expense for each business unit as a part of the calculation of income from each business element. The Port still does not do so. Residents also have asked the Port for years to show the property tax revenue separately from the calculation of net income so that residents can see how the Port’s actual operations are doing. The Port has declined to do so.

False job numbers

Maybe you’ve heard this: “The Port of Olympia creates 5,000 jobs.” It’s all spin. The Port counts every job of every person working in every building located on port land. For example, the “erector set” building just North of the Farmer’s Market (111 Market St. NE) is built on leased Port land. Merrill Lynch has its offices on the third floor. If that building did not exist, they would rent space somewhere else. But the Port counts those jobs — and a spinoff multiplier from those jobs — as “created by the Port.“

A spinoff multiplier in economics measures the broader ripple effect of a new venture—or “spinoff”—on the wider economy, including indirect and induced effects, by quantifying how initial spending or job creation in the new company generates additional jobs, income, and economic activity in other businesses and sectors. Essentially, for every dollar invested or every job created by the spinoff, the multiplier shows the total economic value generated, demonstrating how it stimulates growth and supply chain linkages throughout the region or economy

Spin-off valuations and their corresponding multipliers are susceptible to manipulation by management. This can be achieved through both quantitative manipulation of financial numbers and qualitative manipulation of the corporate narrative presented to investors.

The Port creates approximately 48 jobs: its staff. That costs us $8 million per year, so about $150,000 per job.

The rest of the jobs that exist on Port property are private sector jobs, and all of these (and more) would exist even if the Port of Olympia went away:

Marine Terminal: If the Port of Olympia disappeared, the City of Olympia or a private business would own the marine terminal. The companies that lease the terminal now would pay rent to the City of Olympia or a private company instead of to the Port. On the other hand, if the marine terminal went away, goods now flowing across the Port of Olympia would instead flow across different ports: Grays Harbor, Tacoma, Seattle Longview, Kalama, Vancouver. The number of jobs would be about the same. For example, if the logs from Vail were trucked to Aberdeen, there would be more truck driver jobs in Washington, but the ship would take 3 days less to do a round-trip to Asia, so there would be fewer ship company employees.

Airport: Someone else would likely operate an airport (There are nine other airports in Thurston County, all privately owned and paying property taxes.) Most likely the state Aeronautics Division of the Washington Department of Transportation would take over the Olympia Airport, as the state is a major user.

Marina: There are multiple private marina operators. They could expand, and one could take over the West Bay marina.

Office Buildings: If the Port put its office buildings up for sale, private owners would buy them, and the tenants would have new landlords.

Of course, if the Port of Olympia went away, the private operators would employ people to manage all of these operations, probably approximately the number employed by the Port of Olympia, which means no jobs even in Port operations would really be lost. And the $8 million now collected in property taxes would remain in the bank accounts of taxpayers. If they spent that money locally, that would create jobs in retail and services locally.

A recipe for financial mismanagement

Ports in Washington state were created under Washington’s Port District Act of 1911. The legislature designed port districts explicitly to engage in commercial enterprises — shipping, marinas, airports, industrial real estate — while also being local governments with taxing authority.

Their enterprise side (marine terminals, real estate, airports, marinas) often looks very much like a private business. Their government side (property tax levies, environmental cleanup, public infrastructure) gives them public funding tools not available to private competitors.

The blend is central to their identity. Ports can directly own, develop, and lease land for private companies — something cities/counties usually do only in limited redevelopment contexts. Ports can levy property taxes to subsidize or backstop those commercial activities, which private firms cannot. Ports are even allowed to use public funds for “promotional hosting,” meaning picking up the tab for drinks and entertainment to court potential tenants.

Washington ports’ governance model almost guarantees waste and conflict with local business. The key is that ports don’t face the discipline of a true business (where losses force closure), nor do they face the checks and balances of a city or county government (which has broader public oversight and responsibilities).

Guaranteed Tax Revenue (“Free Money”)

The first problem with the governance model is that ports lack pressure to be frugal or truly profitable. Every port can levy property taxes regardless of its commercial performance. This ability to tax cushions losses and removes market discipline that private businesses must face.

Unfair Competition with Small Businesses

The second problem is that ports can use the free tax money to undercut local businesses. Ports can develop marinas, office space, warehouses, and industrial parks, subsidizing them with tax revenue. Local businesses may be forced to compete against a publicly funded business entity with deep pockets.

For example, the Port of Olympia put in a boat fueling station using taxpayer dollars. This is causing economic harm to the Boston Harbor Marina, a local small business that had previously been the nearest fueling station.

High Debt Loads

Ports often take on long-term debt for projects that don’t generate enough revenue to cover the debt service. Taxpayers end up paying for both operating losses and debt repayment.

Accountability Gap

Because ports are “special purpose districts,” they don’t get the same public scrutiny as cities or counties.

Budgets are technical, financial reports are opaque, and public attention is low — so mismanagement can persist.

Is there a solution?

In the near term, the solution for Thurston County is to elect candidates of change over candidates of the status quote. Krag Unsoeld’s opponent was hand-picked by the current Port elected leadership and is part of an advisory committee to the Port Commission. Jerry Toompas’s opponent is on the commission now and voted to raise our taxes. Neither of Krag or Jerry’s opponents represents the change we need.

In the long term, legislative reform is needed. In other states, ports are run as either state-level port authorities or municipal enterprises under a city or county. They don’t get a permanent property tax subsidy to backstop losses.

As a result, ports in other states do not create the same problems as ports here do. If Washington wanted to fix the problems with the Port District Act, the cleanest solution would be to strip Washington ports of their independent taxing authority and require them to operate like ports elsewhere in the U.S. There are ways this could be done, but that is beyond the scope of this article.

Jim Lazar is a retired economist. Ronda Larson is a local attorney.

This is the clearest explanation of Port financing and the problems that arise from the self-governance model that I have seen. Time to change the Port District Act.