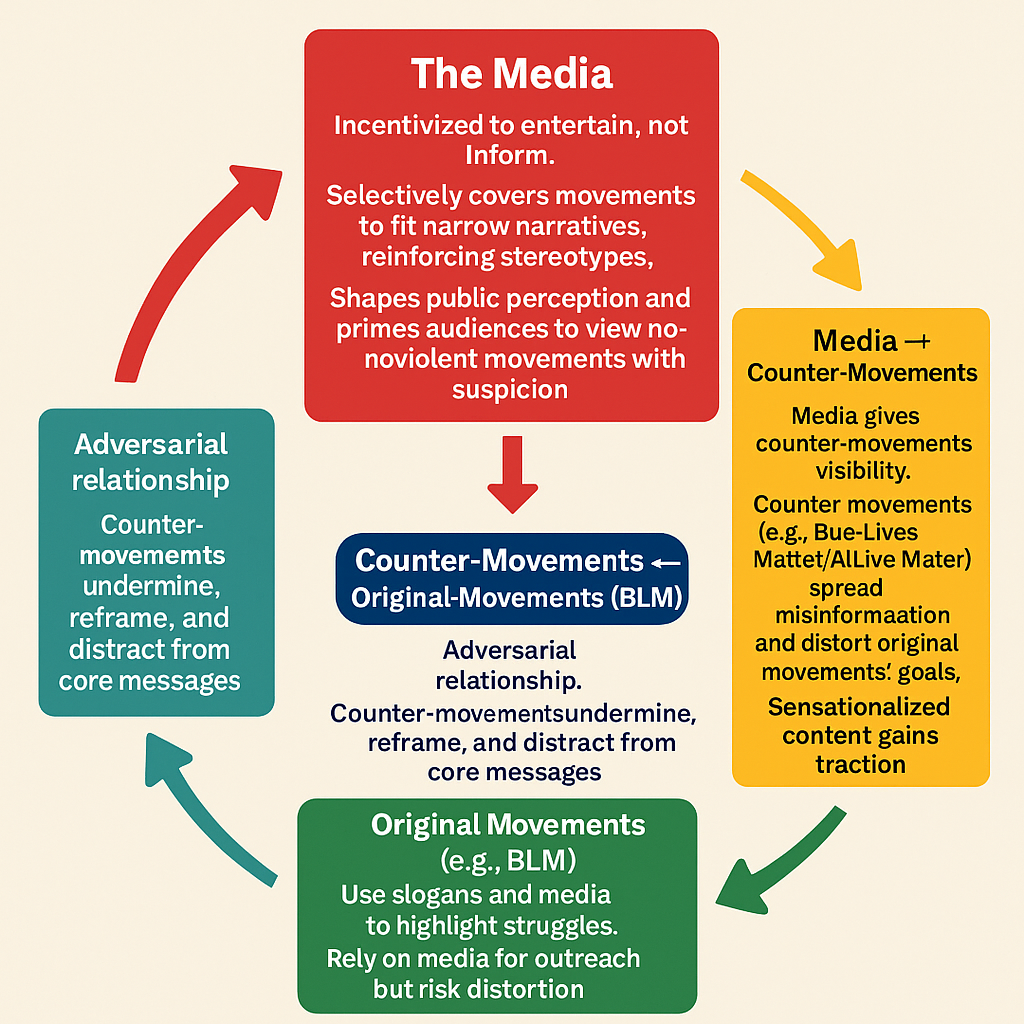

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement began as a plain moral claim: Black lives matter, in response to systemic racism and police violence. Yet as its visibility grew, its core message was bent by selective framing, politicized counter-slogans, and a media ecosystem incentivized to polarize. The distortion is not accidental noise; it is a form of cultural violence in which language, symbols, and narratives legitimize repression and hide structural harm. Understanding how we arrived here, and how to fix it, requires looking at media practices, the rise of counter-movements, and the regulatory void left by the elimination of the Fairness Doctrine.

Framing Nonviolence as Disorder

News coverage of BLM often leaned on the “protest paradigm,” emphasizing conflict, disruption, and crime while sidelining the movement’s aims. Labels such as “riot,” “chaos,” and “public nuisance” or the recent efforts to rename the “No Kings” protests as “Terrorist demonstrations”, or as the “Hate America rallies”, all for the purposes of framing nonviolent dissent as a threat. This language both criminalizes protesters and normalizes an aggressive police response. The effect is not merely reputational; it lowers the political and social costs of repression. When the public is convinced a movement is violent, backlash to state crackdowns fades.

Counter-Movements and Competitive Victimhood

Counter-slogans such as All Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter sound inclusive or protective but operate rhetorically to erase the specific harms BLM addresses. They redirect attention from systemic racism to police vulnerability, recentering state authority as the aggrieved party. The result is a powerful counternarrative: protest becomes menace, accountability becomes persecution, and the emblem of a nonviolent movement is crowded out by symbols and stories that cast it as illegitimate.

Cultural Violence: The Quiet Engine

Norwegian sociologist, Johan Galtung’s framework on what constitutes violence might help explain this situation. Direct violence, he says, is the visible harm, such as police brutality. Structural violence is embedded in institutions and laws that deny the full flourishing of human lives. Cultural violence is the story we tell that makes the first two seem inevitable or justified. In coverage that fixates on broken windows but obscures broken systems, cultural violence does its quiet work, presenting inequality as order and dissent as disorder.

Galtung’s three dimensions—direct, structural, and cultural violence—together illuminate how harm against Black communities is perpetuated and normalized. Direct violence manifests through police brutality, while structural violence is embedded in biased institutions that perpetuate marginalization, such as discriminatory law enforcement and judicial systems (Bertilsson 2021, 38). Cultural violence legitimizes these injustices by framing Blackness as threatening and resistance as disorderly, particularly through skewed media narratives. This cultural framing reinforces structural violence by shaping public perception in a way that normalizes inequality and justifies direct harm. For instance, media portrayals that depict Black Lives Matter protests as violent create a climate in which excessive policing is accepted or even expected. This cycle of harm is reinforced by poverty, racial profiling, and underrepresentation in leadership roles, all of which reduce the potential for full realization of well-being within Black communities (Bertilsson 2021, 39). Therefore, dismantling police violence and its systemic roots demands not only institutional reform but also a shift in cultural narratives and public consciousness that sustain racial hierarchies.

Why the Media Became So Susceptible – The Collapse of the Fairness Doctrine

Part of the answer is structural. Routinized news practices prioritize official sources, conflict, and spectacle. But part is regulatory. For nearly forty years, broadcasters in the United States operated under the Fairness Doctrine, established by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 1949. The policy required license holders, when addressing controversial issues of public importance, to provide a reasonable balance of significant opposing viewpoints. It did not demand equal airtime, but it did require good-faith efforts to ensure diverse perspectives.

This principle was reinforced by the Supreme Court in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC (1969). The Court held that the First Amendment exists not only to protect speakers but to safeguard the public’s right to an “uninhibited marketplace of ideas.” The ruling emphasized that citizens must have access to a broad range of political, moral, and social perspectives and that neither government nor private licensees may monopolize the public conversation. In effect, the decision treated broadcasters as trustees of the public interest, obligated to use scarce frequencies for the public good rather than narrow agendas.

That framework collapsed in 1987 when the Reagan administration and conservative interest groups pressed the FCC to repeal the Fairness Doctrine. The justification was that deregulation would enhance free speech and open a more competitive media market. Instead, the repeal produced a fragmented landscape where broadcasters no longer had to offer balance. What followed was the rise of highly partisan talk radio, the growth of ideologically segmented cable news, and the erosion of shared reference points in American civic life.

The long-term consequences have been profound. Without the guardrails of the Fairness Doctrine, partisan silos flourished. Networks now operate more as brand-loyal communities than as neutral information providers. Audiences are funneled into echo chambers where algorithms and programming choices reinforce preexisting beliefs while walling off competing perspectives. Pew Research Center has documented how sharply this shapes public perception. For example, consistent conservatives overwhelmingly trust Fox News, while consistent liberals rely on MSNBC or NPR. At the same time, most Americans report encountering political news they find biased or untrustworthy, and trust in national outlets has fractured along partisan lines (Pew Research Center, 2020).

This identity-based polarization does more than entrench bias. It hardens partisan loyalty into moral identity, where disagreement feels like betrayal and opponents are framed as existential threats. The January 6th Capitol attack illustrated how disinformation amplified by partisan outlets can spill into political violence. Studies also show that false political headlines spread more quickly on social media than factual ones, magnifying the danger in a deregulated environment.

In short, the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine stripped away a critical safeguard for balanced dialogue. Instead of cultivating civic debate, American media became a patchwork of echo chambers, where truth competes with sensationalism and democratic discourse suffers. Restoring some form of balanced reporting standards may be essential to countering polarization, reducing disinformation, and rebuilding public trust in journalism.

Trusteeship: A Better Ethic for Public Discourse

To address the ethical vacuum in modern media, it is helpful to turn to the insights of Mahatma Gandhi, the father of nonviolent action and a foremost thinker on nonviolent communication and public discourse. Gandhi proposed the idea of trusteeship as a moral framework for corporations and capitalists—arguing that those who control wealth and power should act not as owners but as stewards of the public good. While originally applied to economics, this concept offers a compelling lens for media ethics today. Those who control scarce public resources such as broadcast spectrum, major networks, or dominant digital platforms should likewise see themselves as trustees—responsible for upholding truth, diversity, and equity over profit and partisan interest. Adapting Gandhi’s principle of trusteeship to the realm of media encourages a vision of journalism and communication not as commodities, but as public trusts essential to sustaining democratic life.

The Backfire Problem and Why Language Matters

Research on civil resistance shows nonviolent movements tend to prevail more often than violent campaigns, in part because repression against peaceful protesters can backfire and trigger loyalty shifts and broader support. But that dynamic depends on perception. When media frames nonviolent action as violent, the backfire effect fizzles. Words do not just describe events; they pre-decide who deserves sympathy, who merits force, and whose story is believed. As Thusi (2020) notes, rhetorical tactics such as citing “Black-on-Black crime” worked to delegitimize the BLM movement and devalue Black lives relative to police lives (Thusi 2020, 24–25). The term “riot” itself operates as a politically loaded mislabeling, often employed to undermine the legitimacy of otherwise peaceful protests. As scholars Chenoweth and Stephan emphasize, such language strategically delegitimizes nonviolent resistance despite empirical evidence showing that nonviolent campaigns are more successful than violent ones, achieving their aims 53% of the time compared to just 26% for violent campaigns (Chenoweth and Stephan 2008, 8).

Labeling peaceful protests as violent not only justifies state crackdowns but also undermines the efficacy of democratic dissent. However, history—from East Timor to the Philippines—demonstrates that disciplined, mass-based nonviolent resistance often produces loyalty shifts within regimes and international support, ultimately leading to political transformation (Chenoweth and Stephan 2008, 25–36).

What Would Fixing a Broken Media System Look Like?

Rebuild guardrails for balance on public airwaves. We do not need a carbon copy of the Fairness Doctrine, but we do need updated standards that require viewpoint diversity on controversial issues where access is scarce. Public spectrum should serve public deliberation.

Adopt newsroom standards that resist the protest paradigm. Treat “riot” and similar labels as claims to be verified, not defaults. Lead with the issue the protest addresses, contextualize isolated incidents, diversify sources beyond officials, and train reporters to spot how framing can stigmatize dissent.

Elevate trusteeship in media governance. Boards and owners should formalize “public-interest covenants” that commit to transparency, source diversity, and corrections as core duties. Treat audience trust as a civic asset, not just a quarterly metric.

Invest in independent and local media. Fund nonprofit, community-anchored outlets that can cover movements with proximity and nuance. A healthier information ecosystem requires plural centers of storytelling power.

Teach peace linguistics and media literacy. From K–12 to newsroom training, equip people to recognize how language shapes reality: what is named and unnamed, whose voice counts, and which frames make injustice look normal. The goal is not rhetorical purity but democratic competence.

Cover movements as movements, not just moments. Sustained reporting on policing, courts, budgets, and policy outcomes prevents “burst” coverage from defining reality. Nonviolence is a strategy with a history, an evidence base, and measurable aims; report it that way.

The Bottom Line

BLM asked the country to confront a basic moral fact: equal worth requires equal protection. Media language and structure too often turned that claim into controversy, that controversy into threat, and that threat into justification for repression. That is cultural violence at work: quiet, deniable, and devastating.

– Repair is possible. Reintroduce public-interest obligations where we can:

– Re-center trusteeship where profits and politics crowd out duty.

– Train journalists to interrogate their own frames.

– Grow independent media that can tell the full story.

– And teach audiences to hear the difference between coverage that informs and coverage that inflames.

Nonviolent movements need fair hearings to do their democratic work. The rest of us need them to succeed.

Mahamed Rage is a recent graduate of the Law and Policy program at UW Tacoma currently preparing for law school. He enjoys reading and writing about issues that impact his community. He is also a policy enthusiast, a Manchester United fan, an intermural soccer player, and an audiobook aficionado, and hopes to one day get one published.

Be First to Comment