An unfinished agenda

[Note: The Evergreen State College celebrated its inauguration and dedication on April 21, 1972 —colliding with a call for a national student strike against escalation of the Vietnam War. Eirik Steinhoff, an Evergreen adjunct faculty member, retrieved Governor Dan Evans’ speech at the event as part of a year-long 50th anniversary inquiry into the past, present and future of the college. The speech is presented here with Eirik’s comments and other material to provide context.]

True to form, and setting a precedent for consequential intersections between “current events” and College business, the Dedication/Inauguration ceremony was visited by what Founding Dean Charles Teske, who spoke at the ceremony wearing a black armband symbolic of protest of the war, called “a crisis of public relations and standing with members of the larger community around us”:

On Sunday evening, April 16, President Richard Nixon appeared on national television to announce that, in retaliation against fresh Viet Cong incursions in South Vietnam, he had ordered the resumption of the bombing of Hanoi and the new bombing of Haiphong. The high-altitude attacks by B-52 bombers flying from Guam had already begun. On Monday, April 17, the National Student Association asked for a Day of Moratorium—a nationwide strike of colleges and universities against the escalation of the War—on Friday, April 21, our day of Dedication/Inauguration. (Uncertain Glory of an April Day)

Speaking at the ceremony, Washington State Governor Dan Evans (who in 1967 signed the legislation that established the College, and was to serve as the College’s second president), made note of another chronological conjunction:

Evans begins: “I think it’s a particularly appropriate date on which we meet here—tomorrow, April 22nd, is Earth Day, or it was a celebration of Earth Day of a couple of years ago and you remember the interest and the nationwide dedication to a quality environment and a better future for this country.

Acknowledging “the turmoil and the activism” by those “who have set out to reorder our priorities and to reorder society,” Evans called on his contemporaries “to reach inward, to reach down and touch the troubled spirit of America.”

Evans relates these insurgent endeavors to what he under-stood Evergreen to stand for:

“It is time to confront the issues of poverty and disease and human dignity, which lie beneath the violence that tears at every conscience just as it strikes fear in every heart. But if Evergreen means anything, if it means anything to the faculty, and to the administration and to the student body, and if it means anything at all, to the citizens of this state, then I believe it must mean that the tackling of this unfinished agenda must be formed, that somehow and in some way what Evergreen does helps to replace helplessness with hope.

Evans proceeds to slide the timeline forward, to imagine the future in overtly utopian terms, and to connect Evergreen to the realization of this vision of abundance, justice, and reconciliation:

“In 28 years, the millennium will have come again. The year 2000 will be here and those of you who are students at Evergreen today, will be my age—heaven forbid. laughter And I think the question you ought to ask yourselves today, and I hope it is being asked by many, is “what will I face then?”

Do you ever really think about it, or do you ever really care? And I think the real question is not what it will be like in the year 2000, but “how can I make it what it should be?” in the year 2000, not for just myself, but for the entire community. If Evergreen is to fulfill its commitment, it as an institution must dream not the small dreams, but the very large dreams.

I hope by the year 2000 that education will be much more individualized and personalized than it is today, and that much of that education will occur in the community and not solely in the separate and sometimes rather isolated campuses of our colleges, universities, and even high schools.

I believe by the year 2000 there will be an extensive interchange of people, from one country and one continent to another, and throughout that exchange and through that better understanding at the person-to-person level perhaps we have the best single hope of reaching a peace that is lasting.

By the year 2000 we must have resolved the basic rights of each citizen of this nation to adequate medical care, adequate food and adequate housing for each citizen.

But most of all by the year 2000, I hope we have reached a society where success is not measured by the accumulation of material goods, but by how satisfying, how useful, and how personally rewarding a life becomes.

[ applause ]

Evans continues:

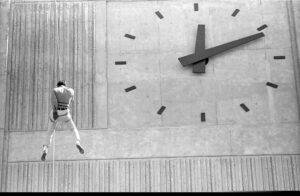

“Some word got around, of this community, that I was going to participate in an unusual event today… [chuckles, audience laughs] William Unsoeld suggested that I rappel down the clock tower. [ audience laughter and applause ]

But in fact an even more improbable mode of locomotion was proposed:

What is vastly more important is that you leave your mark on Evergreen. To President McCann, to students, to the faculty members of this college—today the potential for doing that is unlimited because you have no footsteps to follow. Tomorrow’s generation will travel in your footsteps, so I hope and trust that each of you will make these first steps innovative, and bold, and decisive, but most of all, make these first steps taken with a conviction that there is a future, that it is not preordained, but that it will be what we make it. That must be the Evergreen challenge. “

The Governor’s remarks were followed by the installation of Charles McCann as Evergreen’s first president.

You can find Teske’s full description of the day in the Evergreen State College Archives.

Be First to Comment