(This article is excerpted from the author’s forthcoming book Unlikely Alliances: Native Nations and White Communities Join to Defend Rural Lands (University of Washington Press / Indigenous Confluences series, May 2017), and draws from interviews with Native and non-Native representatives.)

The Bakken Oil Shale Basin centered in North Dakota is the source not only of the Dakota Access Pipeline, but also skyrocketing numbers of crude oil trains that traverse the continent, including the Pacific Northwest. In 2008, Washington and Oregon refineries began to receive rail shipments of fracked crude oil from North Dakota, at first to ship not overseas (due to a 1975 crude oil export ban that was recently overturned), but to West Coast refineries. According to the Sightline Institute, if all Northwest oil, coal, and gas projects proceeded, they would cumulatively ship the carbon equivalent of five Keystone XL pipelines.

From 2008 to 2013, the number of oil railcars coming to Northwest facilities increased more than 4,000 percent, and the industry proposed more port terminals. Bakken crude is more gaseous and volatile than other oil, so when the oil trains derail they have erupted in huge explosions, such as the Quebec fireball that killed 47 people in 2013. There were more oil train spills that year than in the 37 years prior.

Up to fifty oil trains a month, each 1.5 miles long, would supply up to three proposed Grays Harbor oil terminals in Hoquiam, where Bakken oil would be loaded into enormous tankers, next to key migrating bird habitat. The Quinault Indian Nation and Grays Harbor residents became concerned about the effects of an oil tanker spill on local fisheries and shellfish beds. Quinault treaty territory extends into Grays Harbor, and the coastal reservation is famed for its pristine beaches, razor clams, and blueback sockeye salmon.

Collaboration between the Quinault Nation and Grays Harbor environmental groups had extended back to 2008, when Joe Schumacker, marine resources scientist for the Quinault Department of Fisheries, was the tribal liaison on the Grays Harbor Marine Resource Committee. He kept contact with the Friends of Grays Harbor and Grays Harbor Audubon, as well as the Citizens for a Clean Harbor, which defeated a proposed coal terminal in 2012, only to face three proposed oil terminals later the same year. A consolidated appeal by the Quinault Indian Nation, Sierra Club’s Earthjustice, and local environmental groups convinced the state Shoreline Hearings Board in 2013 to revoke Washington Department of Ecology permits for two of the oil terminals, pending a state environmental impact statement.

Nearly unanimous public opposition began to emerge in 2014 during a series of Department of Ecology hearings along the proposed oil train route. On the morning he passed away that year, Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Chair Billy Frank Jr. supported the Quinault stand in his last blog: “It’s clear that crude oil can be explosive and the tankers used to transport it by rail are simply unsafe. . . . Everyone knows that oil and water don’t mix, and neither do oil and fish. . . . It’s not a matter of whether spills will happen, it’s a matter of when.” Fawn Sharp, President of the Quinault Indian Nation, agreed: “Not all the oil gets cleaned up, no matter how good the effort. That oil affects the habitat, and can make it uninhabitable by fish for decades.”

The Grays Harbor community had historically been hostile to outside mainstream environmentalists, whom they blamed for the closure of local timber mills during the Northwest “spotted owl wars.” Working only with Earthjustice would reinforce that perception, but Quinault leaders made a point of working also with local environmental groups and fishermen and pushing a “no oil trains” message on local billboards and in newspapers. As Quinault Vice President Tyson Johnston commented, “[Some local residents] will lump us in too with a lot of the environmental groups, and we do carry a lot of those values, but we’re in this for very different reasons such as sovereignty, our future generations.” Quinault leaders also point out that climate change, generated by the burning of fossil fuels, has detrimentally affected salmon and shellfish for both Quinault and non-tribal fishers.

The Quinault Nation had usually been at odds with the Washington Dungeness Crab Fishermen’s Association, which has challenged treaty-backed crab harvests. But as Association vice-president Larry Thevik pointed out about the oil terminal issue: “[It has] united us in the preservation of the resource that we bicker over. It has also kind of created a new channel of communication because those of us at the bottom of the food chain, the actual fishers, have been able to talk somewhat directly to another nation.” Schumacker, the Quinault Nation marine resources scientist, agreed: “With no resource, there’s no battle . . . we have to maintain what’s out there. Those people, those local crabbers out here are almost as place-based as the tribes. I will never say that they are as place-based, but they feel so deeply rooted here and it’s part of their lives. . . . We find ourselves working together on these matters.”

Quinault President Fawn Sharp (also President of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians) was born in 1970, “at the height of the fishing rights conflict.” She commented: “I was a young child, but was very impressionable. At eight years old, I understood what treaty abrogation meant, that there were others trying to wipe out the entire livelihood of not only my family, but my larger Quinault family. That was very real. My perspective is a product of that era.” She remembered being called names in neighboring communities and her family’s tires being slashed. Even as late as 2000, when she testified for a fisheries enhancement project, “some irate sports fishermen in the audience” kicked her chair.

Sharp reflected: “Part of the relationship that we have today arose out of generations of disputes. Through those disputes, whether they liked us . . . didn’t like us . . . they came to know and understand Quinault and our values. . . . For us, a lot of the relationships we have with our neighbors arose out of a relationship of much division, strife, and conflict, but through that . . . they’ve come to know who we are. That, to me, is a foundational bit of understanding.”

Sharp was later impressed, however, in meeting Larry Thevik and other local crabbers when they worked for a renewable energy project and against a coal terminal and agreed to work together with Quinault even as they disagreed about crab harvest allocation. When the oil terminal issue emerged Sharp thought, “We need to develop these partnerships because this oil issue is so much larger than Quinault Nation.” Adding a “footnote of hope,” she said: “The cooperation that we’re seeing now is going to provide another sort of step of maturity and good faith and alliance and looking beyond special interest or individual interest to the greater good. Perhaps today’s generation and younger people growing up in this political climate will come to understand that it is so much better to work together with neighbors.”1

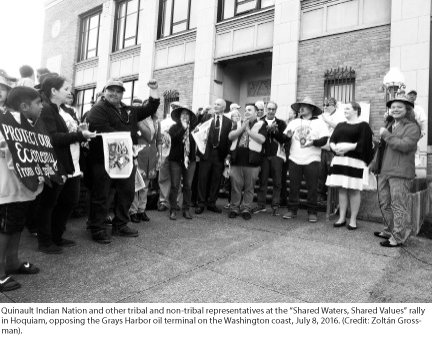

Last March, Sharp and Thevik published an editorial portraying crude oil as a risk to the fishing and tourism industries and pointing to 57 percent opposition among Grays Harbor County residents. By then, two of the three Grays Harbor oil terminals had been dropped, and the third was under sustained public pressure. In July, the Quinault Nation sponsored the “Shared Waters, Shared Values” rally, including a flotilla of fishing boats, tribal canoes, and kayaks. Notably, the rally’s roster highlighted tribal and other local speakers, and none from outside environmental groups.

Quinault has begun to explore sustainable economic options to crude oil in collaboration with other Grays Harbor County communities. Students in the Evergreen program “Resource Rebels: Environmental Justice Movements Building Hope” interviewed local residents and compiled their ideas for sustainable jobs (in industries such as tourism, port exports, forestry, and fisheries), in a Winter 2016 report entitled Economic Options for Grays Harbor.

The final decision on the Grays Harbor oil terminal is with the City of Hoquiam and the Department of Ecology. However their decisions come down in the coming weeks and months, it will have been a tribally led alliance that turned around public opinion in Grays Harbor County, and put the oil companies on the defensive. President Sharp concludes, “When we’re confronted with issues like this oil terminal, where it’s all about corporate greed . . . I think we can help lead and understand with our values system . . . proven through centuries. It’s just my hope that future generations, including our own, will go back to that value system that we have of interdependence and interrelationships. There’s so much more positive that can come out of coming together than all of that time, energy, headache, heartache that’s extended in conflict and disputes. If we could focus on the greater good and very broad vision for what we want for our children, we’ll all be so much better off.”

Zoltán Grossman is a member of the faculty in Geography and Native Studies at The Evergreen State College: http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz

Links for more information:

Quinault Indian Nation Environmental Defense facebook page www.facebook.com/QINDefense

Quinault Indian Nation, “Let’s Keep Grays Harbor Safe from Crude Oil,” www.quinaultindiannation.com/crudeoil.htm

Citizens for a Clean Harbor,

http://cleanharbor.org

Railing Against Crude blog,

http://cleanharbor.blogspot.com

Friends of Grays Harbor

http://fogh.org

Sightline Institute,

http://sightlineinstitute.org

Stand Up to Oil,

http://www.standuptooil.org

Fossil Fuel Connections,

http://www.fossilfuelconnections.org

Economic Options in Grays Harbor (Evergreen’s Resource Rebels program), http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz/GraysHarborReport.pdf.

Be First to Comment