Behind the scenes in the business of medicine

The advent of a pandemic virus showed us in vivid terms that our healthcare system is a mess. The US response to the coronavirus has been disorganized, characterized by misinformation and confusion—and resulted in more deaths and infections than in any other developed country. And it’s not over yet.

The advent of a pandemic virus showed us in vivid terms that our healthcare system is a mess. The US response to the coronavirus has been disorganized, characterized by misinformation and confusion—and resulted in more deaths and infections than in any other developed country. And it’s not over yet.

We have learned a lot about what’s essential in an epidemic—because it was missing. Diagnostic tests, high filtration masks, shields, gloves, ventilators: nonexistent in some locations, in short supply in others, or available only for prices 5 to 10 times the normal rate.

Also missing: a coordinated, systematic approach from public health and political authorities. Will tests for the infection be free? Will treatment of Covid19 be free or covered by insurance? No one is certain. Several thousand medical workers responding to the outbreak in the United States have been infected. Dozens have died. Those who spoke out have been threatened, punished or fired.

Many people are now focused on creating a system that promotes health and provides care for all who need it because the need is so apparent. Our existing system is deadly. To plan a future that is better, however, we need to understand the past actions that led to our current system. How did we get to this place?

In 2019, the medical industry accounted for $3.65 trillion dollars of spending nationally. That bill keeps growing as players in the health business find additional ways to cash in on the lucrative medical market.

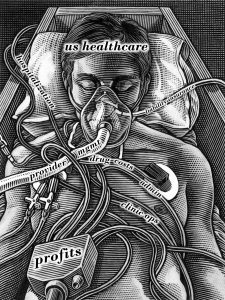

The search for maximum profit leads to abandonment of areas where there is no wealth to extract, even as medical costs everywhere continue to grow. Most of us know nothing about the companies that drive the costs and therefore determine who is able to access healthcare—and who isn’t.

What we have isn’t a healthcare system. It’s a marketplace. It prioritizes profitability, not health, and directs both its services and its rewards to the rich and powerful. Executives command multimillion dollar salaries; investors reap dividends. The result is a destructive mix of deprivation and excess. The current public health crisis has simply made those realities more visible.

Some key sectors of the medical business:

Pharmacy and biotech companies raked in almost a half-trillion dollars in 2018. They protect this income stream in a number of ways. They proliferate patents to extend their monopoly on various drugs. This prevents development of generic versions that could be offered for a lower price. They raise prices on their most-prescribed drugs (40-70% in a recent 4-year period). They promote profitable specialty and “life-style” drugs while doubling or tripling the price of essential medications. Consider insulin: some diabetics pay as much as $400 a month despite the fact that even “new versions” of insulin are cheap to produce.

At the same time, biotech companies scorn research into vaccines and antibiotics that support public health but promise little profit. Work on the antibody test that could be useful as we move away from the coronavirus peak is being done by universities and research institutes. (Once that work is complete, Big Pharma will be there to sell it.)

Medical device and equipment companies

These are another important profit-driven cost generator in the medical industry. Typically, they focus on complex devices that use advanced technology and generate high profit margins. [See sidebar.] In the last few years, consolidation among device companies helped them maintain control over pricing. As one analyst noted, “2018 was a fantastic year, with at least a dozen medical device companies racking up stock gains of more than 25%.”

Hospitals and hospital systems

As in other sectors, hospitals are consolidating to shore up profit margins. More than three fourths of US hospitals are “non-profit” but they are not different from for-profit hospitals in our money-oriented medical system. Both systems are driven by the same motives: expand in size and visibility, increase market share, lay off staff, drive up executive compensation. Consolidation of hospital systems has produced executive compensation in the multi-millions, while pay and respect for workers who provide the service is always under threat. [See sidebar]

The law of profit is unforgiving. If consolidation doesn’t offer attractive rewards, closure can. In Philadelphia, a hedge fund purchased a busy academic safety-net hospital and then closed it in order to sell the land for development Hospitals in rural areas and smaller cities aren’t options for merger—they struggle merely to stay afloat, cutting staff and providing less care. Hundreds of rural hospitals have closed in recent years, leaving millions of people without necessary health services.

Hospital billing practices are also shaped by profit concerns. Rates for the same treatment vary wildly across the US and the actual amount charged is a function of who is paying. Hospital billing is an art-form that accounts for 18% of hospital costs—and allows for differential collections from Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers and individuals. Hospitals—including non-profits—pursue unpaid bills aggressively, even putting liens on patients’ homes. Not surprisingly, medical expenses are the leading cause of bankruptcy in the US.

A recent development in hospital management is the advent of “physician staffing companies” who, in effect, rent out doctors to hospitals—for a profit. About a third of hospital emergency rooms are staffed by doctors on the payrolls of two companies owned by Wall Street investment firms. (The Bellingham doctor fired for speaking to the press was an employee of one of these companies.)

Doctors

Given the role of money outlined above, it shouldn’t be surprising that the US medical industry skews toward specialties, not general practitioners. Most medical school graduates in the US practice as specialists. About 33% become primary care physicians, a number that has declined over time.

Orthopedic and plastic surgeons are at the top of the medical specialty income scale with earnings at almost $500,000 annually. Public health preventive medicine and family practice are at the bottom, earning around $200,000 or less. The availability of primary care is further limited by the uneven distribution of practitioners; by lack of insurance to help pay for visits; by lack of coverage for preventive care; and by practices that are not open to new patients because those patients have government insurance.

Insurers

Our private/public/employer system of “insurance” as a way to pay for all of the above (and more) isn’t working. As more entities enter the medical arena, more cost and more profit is built in, and insurance premiums go up. Private insurers constantly redesign their “products” to limit coverage and refine their administration of benefits to reduce payouts.

Insurers spend 20% of their premium dollars on administration—determining eligibility, utilization controls (e.g., prior authorization of particular procedures), claims processing, and negotiating fees with each and every physician, hospital, surgical centers among other facilities. By comparison, Medicare and Medicaid have administrative costs in the 2-3% range.

More expensive but not better

We are told that our system is more expensive than any other country because it’s better. In the recent words of President Trump, “the virus won’t have a chance against us…we have the most advanced healthcare.” Not true.The US now has more confirmed deaths from the coronavirus than any other country. Beyond the crisis, the US ranks below most developed countries in terms of key health indicators.

Repeated studies by the Commonwealth Fund put the US last or near last of 11 democracies in health access, efficiency and equity. Life expectancy in the US is lower than that of many other countries and infant mortality, notoriously, higher. Disaggregated by race, US infant mortality rates are even worse.

We are told that we spend more than any other country because we overuse the healthcare system. Again, not true. Turns out that we make fewer doctors’ visits than peer countries.

Another world is possible

We can identify the elements of a health care system that would serve us better than the medical industry we rely on now. Health care would not be marketed as a consumer good, but provided as a public good. That’s what the coronavirus has made clear: all members of the society benefit from every member having ready access to care that will keep them healthy. A health care system would prioritize health; it would not ration care by price; and it would be widely accessible.

There are indications that pursuing healthcare as a public good is becoming possible. Obama care as originally proposed included a standard set of benefits to be included in all insurance coverage; it provided for universal coverage; it included a “public option” that could have been a first step toward a single-payer system.

In 1996, Congress created Federally Qualified Health Centers, community-based clinics that provide comprehensive primary care and preventive care, including health, oral and mental health/substance abuse services to everyone regardless of age, ability to pay or health insurance status. These could become the center of a system that supports health and the people who deliver care.

Bethany Weidner served as Deputy Commissioner for Health Policy in the Washington State Office of the Insurance Commissioner from 1993 to 2000, and as manager of Seamar Clinic, an Olympia-based FQHC from 2000–2004.

Sources. Sources consulted for this article include The AMA Journal of Ethics (“A Single-Payer System Would Reduce U.S. Health Care Costs,” Ed Weisbart, MD; Boston Review, “What the Healthcare System Gets Wrong,” Adam Gaffney, MD; The National Center for Biotechnology Information; “An Overview of the Medical Device Industry,” The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission among many others. The Lown Institute, a nonpartisan think tank advocating and acting for a just and caring health system is especially worth a visit for the variety and excellence of the information presented there:

www.lowninstitute.org

Be First to Comment