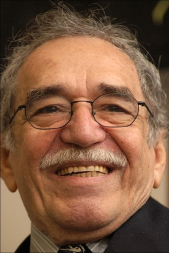

To many, Gabriel Garcia Marquez is the most important writer in Spanish literature, more important than Cervantes. His main work, One Hundred Years of Solitude, has become canonical not only in western literature but in the universal republic of letters. The history of the Buendia family transcended time and place and came to be the history of all of us, human beings hoping to live life, as it should be, a little better. One Hundred Years of Solitude became “la novela total” (The Total Novel).

American pop-culture, just like any other culture, has generational referentials i.e. where were you when Kennedy was assassinated or when Armstrong walked in the moon? Growing up in Latin America in the 60’s—the novel was first published in 1967—the questions were: how old were you when you first read One Hundred Years of Solitude? And what did you think of it? The answers of course would shed light on how soon or late you became aware of your Latin American identity.

The literary and the political (and the dinosaur)

Latin America during the 60’s and 70’s, like the rest of world for that matter, was living under the spell of the immediacy of the revolution. It was close enough that we could practically see it. There was Vietnam, and the third world liberation, anti-colonialist movement. The French student rebellion of ‘68 and the massive European trade unions protests. There was the counter-culture and civil rights movement in the US. There was the example of Cuba and the guerrilla. Politically the subaltern was finding its voice through the writings of intellectuals like Franz Fanon in the Wretched of the Earth, the Letter from a Birmingham Jail by Martin Luther King, the speeches of Fidel Castro and the guerrilla manuals and journals of “Che” Guevara. Of course all these were developed under the conceptual framework of Marxist theory.

In literary terms, the Latin American voice was simultaneously being constructed and heard through that cultural phenomenon known as the “Boom” (The Explosion) with writers such as Julio Cortazar, Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, Jose Donoso, and Agusto Roa Bastos among others. Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude engulfed all these voices and made them resonate at a literary level where it was hard to imagine how to write anything better, both for Marquez himself and the other writers.

Nevertheless, Marquez’s acceptance and well-deserved recognition as a writer in the official corridors of literary power—he won the Nobel Prize in 1982—has always been accompanied by either open resistance, opposition, or silence about his political views. A recent example comes in the words of Ilan Stavans of The New Republic two days ago: “ As savvy as he was in literary terms, in his politics he was a dinosaur.” Here is the dinosaur speaking at the Nobel Prize reception in Stockholm:

Eleven years ago, the Chilean Pablo Neruda, one of the outstanding poets of our time, enlightened this audience with his word. Since then, the Europeans of good will—and sometimes those of bad, as well—have been struck, with ever greater force, by the unearthly tidings of Latin America, that boundless realm of haunted men and historic women, whose unending obstinacy blurs into legend. We have not had a moment’s rest. A promethean president, entrenched in his burning palace, died fighting an entire army, alone; and two suspicious airplane accidents, yet to be explained, cut short the life of another great-hearted president and that of a democratic soldier who had revived the dignity of his people. There have been five wars and seventeen military coups; there emerged a diabolic dictator who is carrying out, in God’s name, the first Latin American ethnocide of our time. In the meantime, twenty million Latin American children died before the age of one—more than have been born in Europe since 1970. Those missing because of repression number nearly one hundred and twenty thousand, which is as if no one could account for all the inhabitants of Uppsala. Numerous women arrested while pregnant have given birth in Argentine prisons, yet nobody knows the whereabouts and identity of their children who were furtively adopted or sent to an orphanage by order of the military authorities. Because they tried to change this state of things, nearly two hundred thousand men and women have died throughout the continent, and over one hundred thousand have lost their lives in three small and ill-fated countries of Central America: Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala. If this had happened in the United States, the corresponding figure would be that of one million six hundred thousand violent deaths in four years.

Very inconvenient truths indeed to be heard by the world, the ears of the well behaved King of Sweden, the members of the Nobel Academy and their spouses; but the point here is to show that Gabriel Garcia Marquez the writer, even at the time of accepting the highest literary recognition in the West, can not be separated from Gabriel Garcia Marquez the human being with a political consciousness.

The simple equation of connecting writing (or the arts in general) with the social is a hard pill both to swallow and digest for a culture where individualism is the King of the Hill, and the social is mostly circumscribed to identity issues, leaving untouched economics, distribution of wealth, and socio-political equity.

Arts, revolution and the public intellectual

Anyone with a modicum of knowledge about Latin American intellectual and artistic history would acknowledge the impact of revolutionary politics – Marxism to be precise– in the life and work of its artists and intellectuals, from openly declared communist poets like Neruda, Cesar Vallejo, Gabriela Mistral, and Jorge Amado, to muralists and painters like Siqueiros, Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Guayasamin, etc., just to mention a few. Garcia Marquez belongs to this continental tradition; not only he was a member of the Communist Party in his youth, but once he reached literary prominence he continued actively participating in socialist and progressive projects as journalist. He also contributed to the formation and development of a socialist party in Venezuela, and remained a loyal friend of the Cuban Revolution. This is the kind of intellectual that we hear very little about when his name is mentioned in literary circles. For Garcia Marquez, life wasn’t separated from politics, just the opposite, as he noted in an interview for the Paris Review mentioned in this week’s Guardian.

On death and After

Ideally we would have liked for Gabo to continue living and writing but as he noticed, “a person doesn’t die when he should but when he can.” He has stopped living and his writing was interrupted due to illness a few years ago, but maybe, just maybe, like Melquiades, one of his famous characters in the elliptical magical realism of his prose, “although he really had been through death, he had returned because he could not bear the solitude.”

Enrique Quintero, a political activist in Latin America during the 70’s, taught ESL and Second Language Acquisition in the Anchorage School District, and Spanish at the University of Alaska Anchorage. He currently lives and writes in Olympia.

Be First to Comment