The war in Syria is the greatest humanitarian catastrophe in the 21st century. What started as an inspirational nonviolent movement for democracy has devolved into one of the most violent civil wars in recent history. At the early stages of the uprising, a popular nonviolent movement emerged and promoted a strategy of peaceful protest and civil disobedience rather than armed insurgency as a means for achieving freedom and democracy in Syria. Unfortunately, this movement was ultimately subverted by both internal and external actors who opted to pursue their political objectives through violence and war.

US supports armed violence in Syria

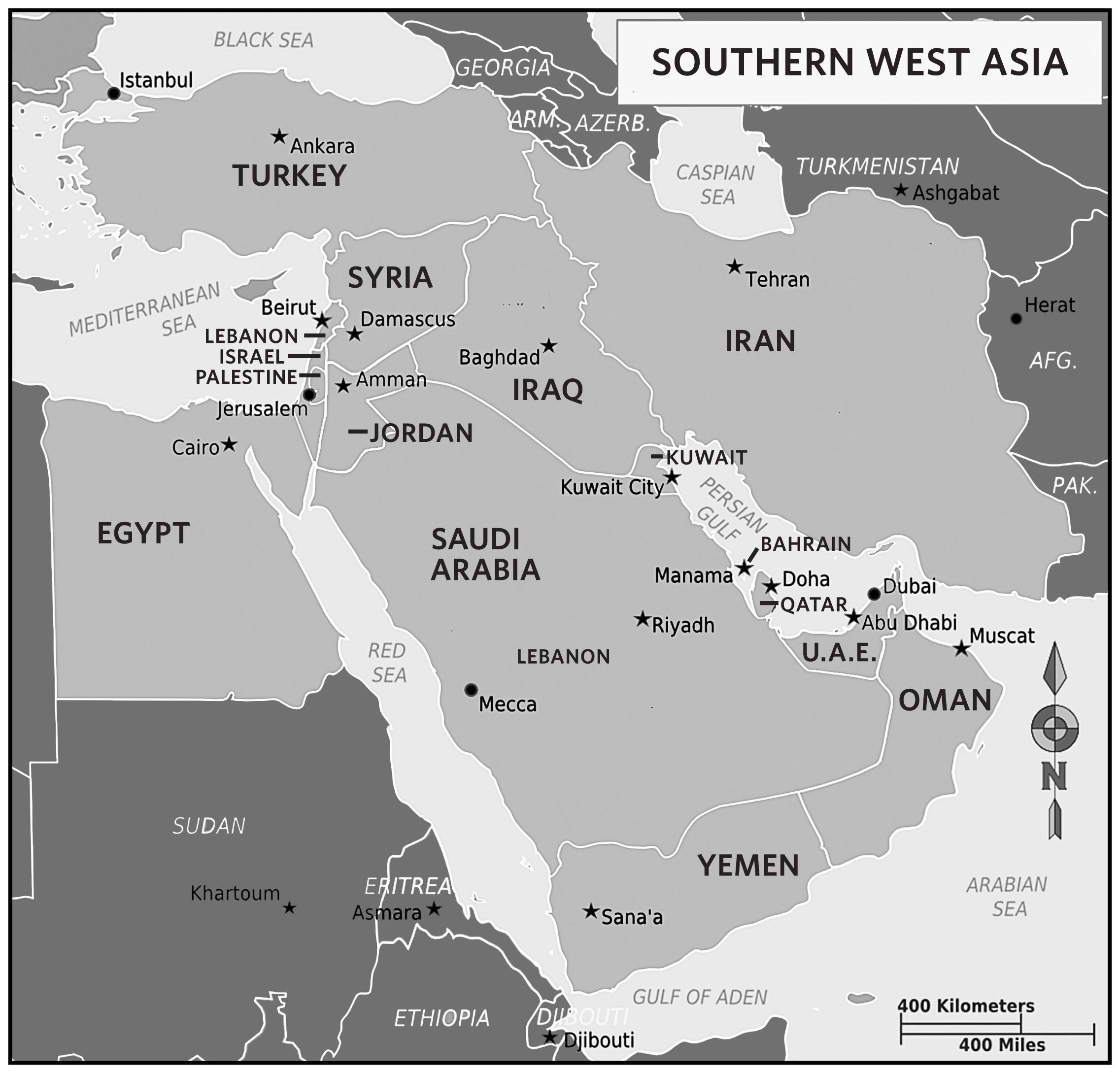

The US government and its regional allies were among those pushing the uprising toward armed rebellion. Within a few short months of the first protests they threw their considerable weight behind those who sought to overthrow the Syrian government by force, with little or no regard to their political orientation or ultimate goals. As widely reported in the mainstream media, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey have funneled billions of dollars in cash and weapons to extremist groups such as the Army of Conquest, which includes the Syrian al Qaeda affiliate known as al Nusra. A leaked 2014 email also revealed that Hillary Clinton was aware that Suadi Arabia and Qatar states had been provided arms and money to ISIL. While the US government officially “condemns” this support for extremist groups, it continues to work closely with these states, operating bases on their territory, selling them massive amounts of weapons, and coordinating strategy in the campaign to overthrow the Syrian government.

This ongoing US policy of regime change in the Middle East has played a central role in fueling the devastating civil war in Syria. Like in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, the US government has targeted yet another Russian-allied foreign government for replacement. It began in the summer of 2011, when Obama declared that “Assad must go.” As reported in the New York Times (NYT) and elsewhere, in a CIA-led covert intervention known as “Timber Sycamore,” the US government began illegally arming and training insurgents fighting to overthrow the government of Syria. The intervention is illegal under both US and international law because it has been carried out without a declaration of war from Congress or approval of the UN Security Council.

CIA trains insurgents outside Syria

As reported in the NYT, the CIA has trained thousands of insurgents fighting to overthrow the Syrian government at the King Faisal Air Base in Jordan. They have also trained thousands of fighters at a base in Qatar, and operate out of a base in Turkey which facilitates the massive flow of arms and heavy weapons pouring into Syria, including portable TOW anti-tank missiles and Grad rockets,* among other sophisticated modern weaponry. In addition to training, money, supplies, and weapons, thousands of jihadist fighters and others from all over the world have poured into Syria through NATO member Turkey, joining ISIL, al Qaeda, or other rebel groups.

ISIL emerges in proxy war

This is how a non-violent “Arab Spring” uprising of masses of Syrians wanting democracy turned into a vicious international proxy war that has killed nearly half a million people, led to the worst refugee crisis since the end of World War II, and destroyed much of the country. This also created the conditions under which ISIL emerged in Syria. Originally operating as an Al Qaeda affiliate within the Western -backed anti-Assad insurgent alliance, ISIL split from the insurgents in 2012 to establish its own ultra-extreme vision of an “Islamic State” in Eastern Syria. Meanwhile, al Nusra remains a powerful force within the insurgents’ ranks, working alongside brigades linked to the Free Syrian Army and at least a dozen other Islamist factions.

With huge amounts of foreign money and weapons behind them, it did not take long for the armed insurgency to completely eclipse the nonviolent movement. Between government repression and the militarization and islamization of the revolution, the nonviolent movement was increasingly marginalized as the insurgency escalated, along with any real prospect for democratic change in the foreseeable future. (The exception here is in the Kurdish controlled areas of Northern Syria, known as Rojava, where the Kurds have established a secular democratic federation of four cantons. The Kurdish organizations in control of Rojava do not seek to overthrow Assad or separate from Syria, but seek to exist as an autonomous state within a national federal structure.)

The rise and fall of the Syrian Nonviolent Movement

Most Syrian people did not have war in mind when they poured into the streets of Damascus on March 15, 2011, to demand democratic reforms and a release of prisoners, nor did the activists and intellectuals that organized the protests. The initial peaceful spirit of the revolution was perhaps best exemplified by the legendary activist Ghiyath Matar, known as “Little Ghandi,” who instead of picking up a gun, handed out flowers and bottles of water to Syrian soldiers, encouraging many others to do the same.

In a report on the Syrian nonviolent movement by the nonviolent action advocacy organization Dawalty, activists recalled that in addition to loud protests that brought thousands of people together, groups organized small ‘hit and run’ demonstrations, colored public fountains red, installed loudspeakers in streets and governmental offices, and played revolutionary songs. They used graffiti and signs to confront the regime’s attempts to label the uprising as Islamist and extremist, for example, one sign read, “if you respect my rights, you’re my brother, whether you believe in God or in a stone statue.”

The rapidly growing popularity of the protests threatened the government, which reacted with brutal repression, including using live ammunition and killing dozens of people. But the government crackdown only inflamed passions, escalating the size and popularity of the movement. Large protests spread to numerous cities. Local revolutionary committees sprang up and began to network with each other, and efforts to build a national coalition that could speak for the revolution begun. The government made a number of concessions, but it was not enough to quell the uprising. All this brought a sense of excitement and optimism that the movement could succeed in removing Assad and open the way to a transition to democracy. Yet despite the initial success of the nonviolent movement, in June 2011 a significant armed insurgency erupted, less than three months from the start of the first major protests.

Hillary and Obama weigh in

The next month, less than four months into the uprising, Hillary Clinton, then Secretary of State, declared that Assad had “lost legitimacy.” Two weeks later a group of Syrian army officers, likely emboldened by promises of foreign backing, defected to form the “Free Syrian Army,” officially announcing the formation of an organized armed rebellion. By August, Obama had given his stamp of approval, and massive foreign assistance began to flow to armed groups. Soon after, foreign jihadists started entering the country through Turkey, eager to take up arms against a secular, Russian-backed regime.

The growing armed insurgency had the effect of splitting the revolutionary movement between those who favored nonviolent protest and negotiation, and those willing to take up arms to overthrow the whole system. Many religious and ethnic minorities who were tolerated under the secular Assad regime—including Shiites, Alawites, Christians, and Kurds—while desiring democratic reform, feared a Sunni Islamist government if the regime completely collapsed.

Fears of Islamization

The insurgency also split the Sunni majority, which makes up about 60% of the population. Most urban middle- and upper-class Sunnis who prospered under the regime opposed the armed rebellion, as did many of those who favored maintaining a secular government. In the words of leading Syrian nonviolent democracy and human rights activist Haytham Manna, “Militarization means Islamization. Ordinary young people want to live; they don’t want to die. They don’t want to bet on a paradise. For that, you need people who will fight to become martyrs. In the end, it will be only the extremists.”

By the end of the summer Syrian society had polarized between those committed to armed rebellion and the downfall of the regime, and those fearing the consequences of armed revolution and Islamization of the movement. Huge pro-government demonstrations in Damascus and Aleppo illustrated that the uprising had already lost substantial popular support, and that many people were opposed to the escalating violence and slide toward civil war. In September, a reported one million people marched in Aleppo in support of the government.

By March of 2012, on the anniversary of the first protests, the nonviolent opposition could only turn out 150 to a march in Damascus, according to activists in the Dawlty report. With weapons, cash, and jihadists pouring into the country, the violent insurgency was rapidly expanding while the nonviolent movement had collapsed to a small core of committed activists and intellectuals.

Today, after more than five years of brutal civil war, most people just want the fighting to stop. There is no longer any popular appetite for revolution, nonviolent or otherwise. Assad is now more popular than revolution, not because people want the regime, but because people are exhausted and traumatized by the war. The insurgent alliance, dominated by radical Islamist groups and plagued by infighting, does not look like anything close to a viable alternative that will bring Syria back from the brink of destruction. As one activist who visited government-held Damascus explained in the Dawalty report, “If someone came out to the streets and shouted out the word, “freedom,” people themselves would stop her before the police could even arrive.” One can only imagine the number of years that will be required for the Syrian people to recover from this monumental catastrophe and again dare to dream of a democratic society.

It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way

Obama and Clinton didn’t have to try to overthrow the Syrian government by force, to train and arm Syrian rebels, or approve the sale of billions of dollars of weapons to Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Qatar, who in turn gave weapons to radical islamist groups. Nor did our Congressional representatives have to support these policies, as Denny Heck and Patty Murray have done. At any time Obama or Congress could have pulled the plug on operation “Timber Sycamore” and stopped the effort to overthrow Assad by force. It was a bad idea to begin with, and as time goes by it has become an increasingly disastrous course of action. Assad is a repressive dictator, yes, but you do not bring democracy to a country by destroying it.

Democracy and a greater respect for human rights in Syria will not come out of a barrel of a gun. The last five years in Syria are a confirmation of this truth. Even if the government did fall, the most probable outcome is that the various rebel factions in Syria would simply turn to fighting each other. This would create a situation like what the US government brought to Libya when it unleashed a devastating air assault that brought down the Gaddafi government, but provided no occupying force to establish security in the country — what Obama has called his “biggest mistake” and eloquently refers to as a “shit storm.” Wanting to avoid this outcome is the reason Obama currently gives for not escalating US involvement in Syria, stating that bringing down the Assad government will require the US to occupy the country, something which the American public is adamantly opposed to.

But we need to go beyond stopping the flow of arms to the Syrian rebels. Instead of the path of illegal regime change and war, our elected officials could choose to pursue a policy of peace. This means respecting international law and working within the United Nations system that was established following World War II for the purpose of preventing another world war. It also means to stop selling weapons to brutal, authoritarian regimes in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Qatar, Egypt, Bahrain, and elsewhere who have little respect for human rights and democracy.

If we curtailed arms transfers to US-backed regimes in the Middle East, it would be in Russia’s interest to do likewise in Syria and Iran, as competing with the US militarily is a losing proposition for Russia in the long run. Our military budget is nearly ten times that of Russia, which spends less on defense than Saudi Arabia. Russia simply cannot afford to keep up with the US militarily. As the world’s wealthiest and most powerful nation, this puts the US is in a unique position to use diplomacy and negotiation to reduce arms sales to repressive regimes in the Middle East and elsewhere. This, combined with diplomatic pressure and support for nonviolent movements, would do far more to foster democracy and respect for human rights in the Middle East than guns and heavy weapons. It would also help create a better safer world for us all.

Jeff Sowers is a high school teacher at East Grays Harbor (alternative) High School, a volunteer with WIP for more than a decade, and a long time nonviolent peace and democracy activist from Olympia, WA. He was active in organizing against the first and second Gulf Wars. Last year Jeff joined the Thurston County Democrats to support Bernie Sanders’ campaign, and is currently serving as a progressive, “Berniecrat” precinct committee officer.

Be First to Comment