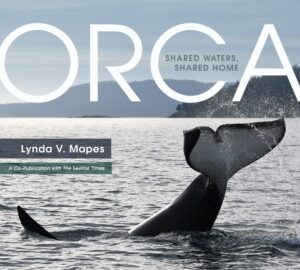

A Co-Publication with The Seattle Times

by Lynda V. Mapes

Lynda Mapes’ book opens with the heart-breaking story of Tahlequah, a member of the J pod who in 2018 touched the hearts of millions of readers as she carried her dead calf, who lived for only 30 minutes, for 17 days and over 1000 miles. Sharing in Tahlequah’s grief, the world was asking why. Why was her newborn calf unable to survive?

In exploring the answer to this question, Mapes expertly blends fact and science with stories of her time spent with scientific researchers and Northwest Native tribal members who are all seeking solutions to the myriad problems compromising the survival of orcas. Shared Waters, Shared Home builds upon an award-winning Seattle Times series, “Hostile Waters: Orcas in Peril” which won top honors in 2019 from the national Online News Association, as well as the National Headliner Award.

In exploring the answer to this question, Mapes expertly blends fact and science with stories of her time spent with scientific researchers and Northwest Native tribal members who are all seeking solutions to the myriad problems compromising the survival of orcas. Shared Waters, Shared Home builds upon an award-winning Seattle Times series, “Hostile Waters: Orcas in Peril” which won top honors in 2019 from the national Online News Association, as well as the National Headliner Award.

Southern resident orcas inhabit the Salish Sea during summer and the J pod is the most frequent visitor to Puget Sound. Despite being listed as an endangered species since 2005, orca populations continue to decline. At the end of 2020, the southern resident orca population totalled just 74 individuals—24 fewer than in 1995.

The book’s narrative is spread across seven short chapters that flow together seamlessly.

Chapter 2 ‘Captives’ details the horrors of the 1960s and ‘70s when orcas were hunted and captured to be kept as entertainment for the public. Pods were herded using firecrackers, corralled into shallow waters, encircled with nets, and the youngsters deliberately separated from their parents. Terry Newby recalls how those that were spared did not flee, but stayed close by, calling to their captive relatives. It hit me. Hard.

The late Tsi’li’wx Bill James, the Lummi hereditary chief, draws parallels between the persecution of orcas and the persecution of the Lummi people. In reference to Lolita, the last orca captured in Puget Sound still living in captivity, Tsi’li’wx Bill James’ description will stay with me. Such pain inflicted on orca and native communities alike:

We understand what happened to her… We can relate to her captivity because of the things that happened to our people. Our young people were taken away from us, just as hers were taken away. That’s how I relate to her, with her captivity, and the government schools taking away our children, and the trauma, taking away our history, our language, our culture, the breaking up of our families. I can feel her heart.

Historic captures were ended (almost) with passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972, and the following chapters explore further threats: hunger due to declining Chinook salmon numbers; noise from shipping, cruise liners and whale watching tour boats; climate change; altered landscapes; degraded habitats; and the release of toxic pollutants from human activity.

Despite the desperate sadness as the many threats to orca are laid bare, the sadness is punctuated by stories of hope and positivity. Most notably, the fact that the northern resident orca population continues to thrive and grow. Mapes dedicates the penultimate chapter to exploring why and how the northern residents are faring better. What can be learned from them and how can we apply this learning to secure a better future for our southern residents?

The main theme running through the book is interconnectivity—between orca, salmon, and humans, but also beyond these individual species to their ecosystem, habitat, and wider environment. As the Coast Salish saying goes; “No little fish, no big fish, no blackfish.” We cannot save the orca without also saving Chinook salmon, repairing their damaged ecosystem and their degraded habitats, and without improving the environmental quality of our region. In doing so we also protect and preserve native communities who rely upon them and who have been seeking to protect them for generations.

Although humans are the main threat to our orcas, this also means that we hold the power to mitigate, remove, and resolve those threats. We can make a difference, we can enact change, and we must better support the survival of our southern residents.

The book ends as it begins, with Tahlequah, though this time it offers hope for the future and a plea for her new calf to live.

Siân Kear is a newcomer to the Pacific Northwest. She ‘happy danced,’ upon seeing transient orcas from the Steilacoom pier in May 2021. She hopes to one day catch sight of our southern residents—happy, thriving, and growing in number!

Be First to Comment