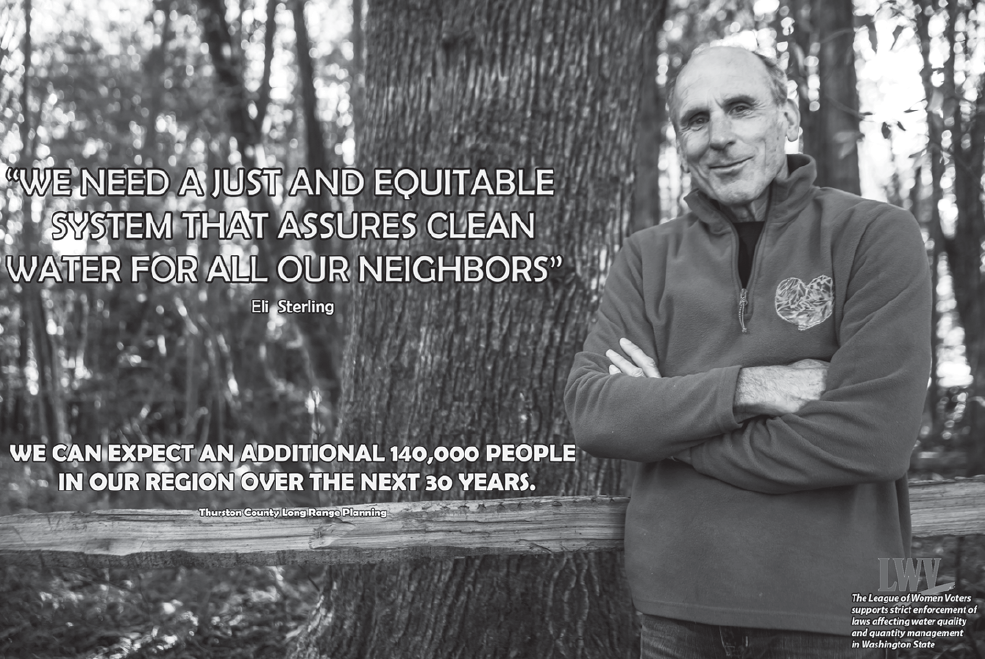

One of the most contentious and fundamental issues facing Thurston County involves water. The laws and regulations around water are complicated and involve many stakeholders. There are tribal treaty rights, federal laws, Department of Ecology regulations, rural communities, municipalities, agriculture, aquaculture and PUDs, all vying for water subject to the State’s Growth Management Act. Add 120,000 people who are expected to move into Thurston County by 2035 along with exacerbating effects of climate change, and the difficulty of ensuring a clean and adequate water supply becomes ever more critical.

The legislature modifies a court ruling

In 2016, a new flashpoint lit up the water wars. A state Supreme Court ruling, known as the Hirst decision, clarified that Washington’s Growth Management Act requires counties to ensure that there is enough water available to accommodate new growth before more development can be permitted. The court’s decision followed basic Washington water law that holds new water rights cannot impair senior water rights, including those of the tribes, the environment, municipalities and farmers.

Tribes have the most senior rights for both water supply and instream flows adequate for fish. With the Hirst decision, rural development was shut down when new wells could not be drilled until counties could verify that an adequate supply of water was present. State legislators from rural areas held the Capital budget hostage last year to compel passage of ESSB 6091, which significantly loosens the Hirst ruling. For instance, it allows new development relying on exempt wells to proceed without a review of water availability. It lacks meaningful limits on water use and does not provide for metering, so the amount of use cannot be monitored. Instead, it provides for committees to develop projects to “offset water use by permit-exempt wells in 15 watersheds” or “water resource inventory areas” (WRIAs).

The committees must develop plans with actions to offset potential effects on instream flows of new domestic wells; and include estimates of cumulative water use impacts for the next 20 years, and result in a net ecological benefit to the watershed.

Thurston County is home to four WRIAs: the Nisqually River Watershed (WRIA 11), the Chehalis River Watershed (WRIAs 22 and 23), Kennedy-Goldsborough (WRIA 14) and the Deschutes River Watershed (WRIA 13). Of these, only the Nisqually has a plan that will be finalized by February, 2019. New committees for the other WRIAs have until 2021 to come up with a plan that meets the approval of the Department of Ecology.

How will stakeholder interests play out?

WRIA 13—the Deschutes Watershed —covers most of Thurston County, including Capitol Lake and Budd Inlet. Its Watershed Restoration Committee consists of representatives from Olympia, Lacey, Tumwater, Yelm, Tenino, Ecology, the Dept. of Fish and Wildlife, the Nisqually and Squaxin tribes, the PUD, Olympia Master Builders, the Deschutes Estuary Restoration Team and the Thurston Conservation District.

This group must balance the needs of growing cities against water rights belonging to streams, farms, aquaculture, builders and industry, and rural residents. Municipalities now use the largest percentage of the available water. That consumption amounts to only 40% of their approved water right, and it is unclear whether there is an adequate supply of water to accommodate full buildout. The databases on water availability are fragmented and inaccurate. The next largest group of consumers of water are aquaculture, then agriculture, followed by industry and residential systems. Individual residential wells account for only a small percentage of overall water use.

Where can water for new development come from?

The stress on the water supply is readily apparent. The city of Yelm already faces water shortages. Most streams in the County run low or even dry up, like Scatter Creek, during the summer. Rising stream temperatures threaten salmon runs and stream life, caused perhaps by denuded shorelines, more surface runoff, septic inflow or volcanic activity. We know that over-pumping of groundwater depletes stream flows. Where will the water for cities and new development come from? The farmers? The fish processors? The mines? Or the streams?

Get your feet wet on Thurston County’s water situation

The League of Women Voters is acting as an observer of the WRIA 13 discussions to protect the public and environment. As part of the update of their 2008 Water Resource Study, which will be used to inform and lobby legislators working on water and planning issues, the League is organizing at least three public forums in the coming months to inform and encourage public engagement.

The first, to be held on February 5 at the Olympia Center, will ask “Where’s the Water? A Reality Check.” Kevin Hansen, hydrogeologist for Thurston County, will explain the relationship between groundwater and instream flows. David Troutt, Director, Natural Resources Department of the Nisqually Indian Tribe will show that “Interstate 5 functions as a dam disrupting the natural flow of the Nisqually River.”

Esther Kronenberg is a member of the League of Women Voters.

Be First to Comment